Usually when I post an art update, I talk about my own work. I’m in the midst of a project that I can’t share right now though because its intended recipients might accidentally see it, so today we’re going to focus on another facet of my creative practice: visiting art exhibitions.

As I learned in my first undergraduate art history class, all art is inspired in one form or another by other art, whether through emulation, rejection, or a combination of the two. I make a point, then, of viewing other people’s work to see how they approach subject, media, and other questions. I wasn’t able to do this very much since the pandemic, but since getting vaccinated I’ve been getting out a little more frequently. During the past few weeks, I’ve been checking out some fantastic art exhibitions, each for different reasons. When I visited The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse at the VMFA, I viewed it primarily as an art historian interested in expanding my understanding of contemporary art from Black artists working in the American South. At Karen LaMonte: Théâtre de la Mode, on view at the Barry Art Museum, I approached it as a curator interested in visiting the physical space of the gallery where Motion/Emotion will be staged.

Today though, I’d like to talk about the exhibition that spoke to me most as an artist: Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful, currently showing at the Chrysler Museum of Art.

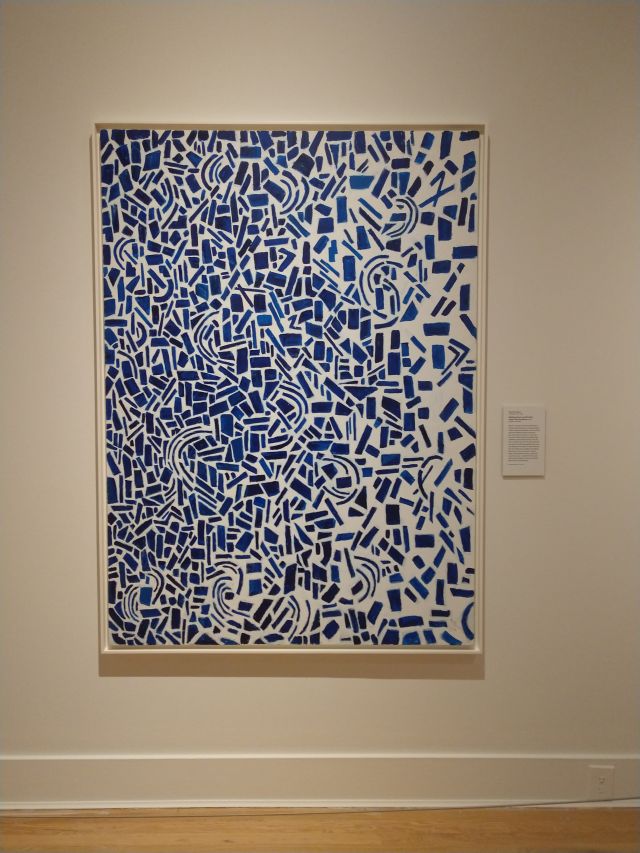

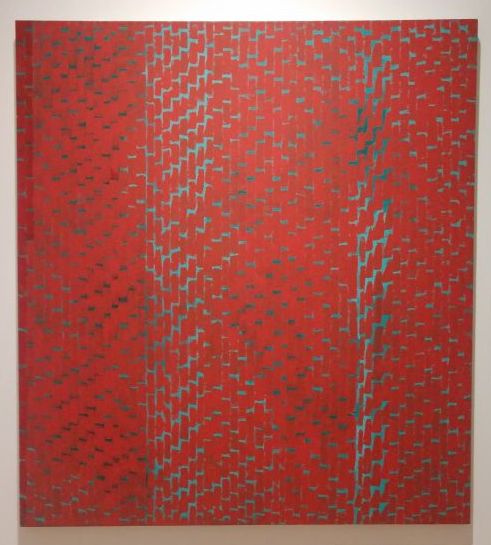

Born in Columbus, Georgia, Alma W. Thomas (1891-1978) was an artist and educator who spent most of her life and career in Washington, DC. She attended Howard University, becoming the first graduate of its newly-formed art department in 1924. For nearly four decades, she worked as an art teacher in middle schools, teaching her students through printmaking, painting, and puppetry. Although she had always studied painting in her spare time, she took up the practice fully after retiring from teaching. While she initially worked in representational styles, beginning in the 1950s she increasingly experimented with abstraction. During the 1960s, after seeing dappled sunlight shining through the leaves of a holly tree from her window, she radically changed her style to emulate the effect, developing the so-called broken brushwork paintings for which she is best known today. Stylistically, these later pieces are affiliated with the Washington Color Field School, though her emphasis on visual brushwork and subject matter rooted in her own lived experiences sets her apart from the group as well.

As a Black woman, Thomas endured systemic racism and misogyny throughout her life, but she rarely references these experiences directly in her work. While she did occasionally paint scenes such as Civil Rights marches during the 60s, and astutely noted how redlining had affected the socioeconomic standing of her neighborhood over her lifetime, overall her painting takes inspiration from more positive memories and interests. Individual works address topics such as her love of gardening, her deep understanding of color theory and the history of modern art, or her interest in astronomy and the space program. Indeed, one of the reasons why she received a solo retrospective at the Whitney in 1972, a time when the institution was being rightly criticized for its over-emphasis on white, male, artists, was because of the seeming apolitical nature of her work, making her a seemingly “safe” choice for the museum. Yet her work remains powerful and significant in its own right, engaging art history, personal experience, and a lifelong interest in learning.

Alma Thomas is admittedly a relatively new artist to me, as I didn’t learn about her or her work until moving to Virginia. I liked her paintings, with their mosaic-like appearance and vibrant palettes, but being able to see them in person was revelatory. I didn’t realize how much depth these pieces had, with Thomas selectively painting lighter hues over darker brushstrokes for a subtle layered effect, until I was able to look at them up close. I also appreciated the variety of mark-making and shapes she used in her later abstractions, with different combinations giving her pieces a rhythmic, musical quality. Indeed, she highlighted the synesthetic character of her work through titles referencing music and sound, from the rustling of wind through autumn leaves to the energetic beats of rock n’ roll.

What I especially appreciated about this show, however, was its emphasis on the other facets of Thomas’s creative practice. For all their appeal and beauty, the exhibition argues, the abstractions for which Thomas remains best known represent only a small part of her total creative output. Indeed, she spent many more decades working as an educator and teacher than she did painting these works, and looking at her career only through the lens of her late paintings does a serious disservice to her oeuvre. Rather than present the paintings in isolation then, the show explores how Thomas’s creative practice manifested through all her myriad interests and activities, from her work as an educator, to her canny sense of fashion, to her ongoing professional and social relationships with other artists.

Within this multifaceted consideration, the show places particular emphasis on Thomas’s work as an educator, pairing her works with those of her students, many of whom she remained in touch as friends or acquaintances. From costumes to marionettes (the latter of which she wrote a Master’s thesis about during the 1930s regarding their didactic potential), this section underscores the multimedia approach Thomas took to teaching. Tellingly, the exhibition centers this education practice by placing it right in the middle of the show, letting all other sections revolve around it. Given the overall disregard given to service-related labor, particularly teaching, it’s refreshing to see this aspect of her work receive so much attention, and if anything, I would have liked to have seen even more of it.

I personally connected to this exhibition in a variety of ways. As a white woman, I’ll never fully understand what Thomas experienced and endured as a Black woman and artist, but I did sympathize with the multifaceted nature of her creative practice. As someone with multiple hobbies and interests, I really connected with the variety within Thomas’s oeuvre, and how she was able to express her creativity not only through painting, but teaching, gardening, and learning. I also really appreciated how she took inspiration from daily life and personal interests for her abstractions. While I don’t paint the way Thomas did, I connected with her ability to transform experiences such as walking through gardens or listening to rustling leaves into vibrant, strikingly beautiful abstract compositions. Looking at her work made me think about how I should revisit some of my own experiments in abstractions, and turn them into more finished paintings. Whereas most art exhibitions I visit in museums engage me as an art historian, this exhibition grabbed me as both a scholar and an artist. After seeing this show, what I most wanted to do was go out and paint.

Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful is up through October 3rd. If you get a chance to visit the Chrysler before this exhibition closes, I highly recommend taking the time to go see it.