The last time we visited the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions, we looked at a textile show based on European crafts. Today, we’ll consider another textile exhibition, now featuring works from East Asia: Oriental Textiles.

Note: English terminology for Asian countries and cultures has changed since the 1930s. Some words commonly used then have become outdated or have problematic connotations. “Oriental” is one of those terms. For this post, I’ll refer to the exhibition by its historical name, Oriental Textiles, as that was its official title. When referring to specific works though, I’ll either use their countries of origin, or East Asia, since all the objects originated from China and Japan.

Historical Background

Like many of the exhibitions we’ve discussed, Oriental Textiles developed out of a larger exhibition, China and Japan: An Exhibition of the Art of the Far East. In 1935, the textile components were separated from the rest of the exhibition and became the basis of a new show, Oriental Textiles. The remaining objects became The Far East, although sometimes it went by other names like Art of China.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen the Met develop two smaller shows out of one large installation. While the museum did create brand-new shows like Ancient Greece and Rome to feature different departments, breaking up larger exhibitions into smaller shows could be more efficient. Not only were smaller installations easier to travel, it enabled the museum to meet its ever-growing list of requests. Demand for the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions increased throughout the program’s duration. Before the initiative ended, the Met had even started looking into erecting semi-permanent installations in parks and other public places because it could no longer keep up with all the requests.

What’s in this Textiles Exhibition?

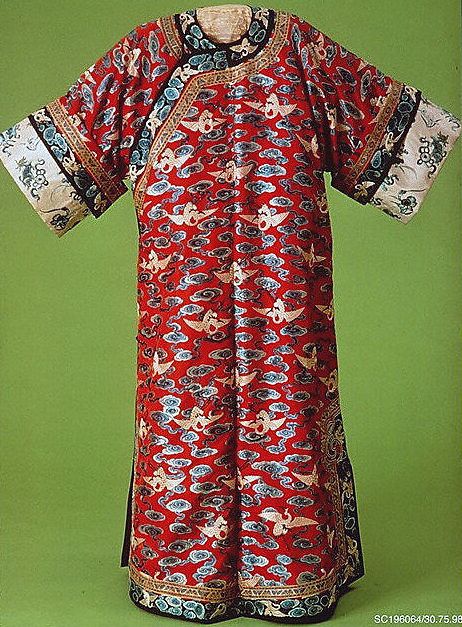

Oriental Textiles included a mixture of small textile samples and full-sized garments such as robes. A checklist for the show as it appeared at Textile High School in 1936 indicates that the exhibition included no fewer than nine robes, four from Japan, and five from China. It also featured 29 additional textiles, as well as a selection of woodblock prints. It wasn’t as massive as Art of Ancient Egypt, which could include more than 500 objects, but at 77 objects, Oriental Textiles wasn’t exactly a tiny installation either.

Although the exhibition focused on textiles, woodblock prints also comprised a significant part of the show’s contents. Featuring landscapes and genre scenes from Hiroshige, Hokusai, and other artists, these prints were likely included to provide context. In studying the prints, particularly if they were figural scenes, viewers could get a sense of how textiles like the ones in the show might have appeared on people. After all, mannequins behave very differently from human bodies, especially when it comes to wearing garments.

My Thoughts on Oriental Textiles

There’s an archival photograph from Oriental Textiles that I really like. You can see it here as part of this slide show. It’s the last photo in the deck (If you’re wondering why I don’t post it here myself, it’s because the Met charges a fee for photo use).

The photo shows students from Washington Irving High School sketching the exhibition. Several students wearing smocks congregate in wooden chairs around the object cases, hunching over sketchbooks as they paint their observations. In the background, another student studies woodblock prints hanging on a wall. All the women appear absorbed in their work.

What I like about this photo is that it attests to the differing ways that the Met and its hosting sites documented the show, and by extension, its impact. Initially, the Met had wanted to send its photographer to document Oriental Textiles on a weekend, when the building was closed. Laura C. Ferris, Chairman of the school’s Art Department, had other ideas. At her request, the photography shoot was rescheduled to a weekday when students would be actively studying the exhibition. Whereas the Met had wanted to focus on the objects and their placement, Ferris wanted to highlight how students actually used the exhibition in their studies.

Dialogues like this remind us that outreach shows such as the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions involve collaboration. Don’t get me wrong, the Met curated these exhibitions; these weren’t community-curated shows. But in scheduling photography times, recommending sites for installation, and maintaining the exhibitions, the personnel at schools, libraries, and other sites also contributed to these shows. In the dissertation, I go into this in greater detail. I discuss the significance of museum and non-museum labor in both the creation of the shows, and the development of museum-community relationships.

So What Happened to the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions?

Based on my earlier comment about the apparent popularity of the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions, you might have a question. What happened to these shows? If they were so popular, why did they disappear?

Basically, World War II happened to these shows. Met personnel always considered the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions an experimental program subject to change or termination as needed. Prior to World War II, the museum intended to continue the initiative while branching into other forms of collections outreach. After the United States entered World War II, however, its plans changed. With the termination of the WPA and the loss of the security and educational personnel it provided, the Met concluded that it could not sufficiently staff the program on its own. In 1942 then, the museum ended its WPA-related activity, including the Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions, stating that it could not sustain these programs without federal assistance.

Next Month’s Exhibition

So that’s it for Oriental Textiles. Next month we’ll circle back to community art centers to consider some of the most frequently-featured works in their FAP exhibitions, the Index of American Design. Stay tuned!