One of my first museum jobs was a summer fellowship at the Old York Historical Society in York, Maine. I held this position during the summer of 2009, between the first and second years of my Master’s program at Williams College. I remember it as a pleasant summer overall. I made some great friends, and I did a lot of different things. I gave tours of various historical buildings, did research on early 19th century processions, and perhaps most memorably, participated in a bit of costumed reenactment. While my subsequent career has not gone down the road of the house museum, that summer was still an important time for me, as it anticipated my eventual shift from medieval and early modern European painting to American art and culture.

I have been thinking about this summer more recently because a lot of my readings on my history list address public history, whether in the form of living museums and reenactments, or historic preservation. in addition to tracing the historical development of these practices, a lot of these texts are addressing the social and economic impacts of these public histories for various communities. In History Comes Alive for instance, M.J. Rymsza-Pawlowska argues that during the 1970s, public history and developed alongside a growing interest looking to history to advocate political agendas. Taking the 1976 Bicentennial as a launching point, Rymsza-Pawlowska explores how a variety of individuals and institutions, from the federal government to more grassroots organizations, looked to historical episodes in an effort to find parallels with the present. Their objectives ranged from promoting patriotism to protesting current policies, as when indigenous groups protested a reenactment of a 19th-century wagon train. Whereas the 1950s and 1960s seem to regard history as both finished, and distantly located in the past, this book posits that the 1970s collapsed the distinction between past and present by appealing to more affective ways of experiencing history, a practice that we continue to see today, whether in the form of living museums, or political invocations to a previous historical era.

Other texts, like the essays in Giving Preservation a History, focus on historic preservation, both as a historical practice and a means of providing economic stimulation to different communities. A key argument in this book, as well as related texts, is that historic preservation is not a neutral activity. The histories that get preserved and just as importantly, the ones that get erased in the form of demolition, say a lot about the society that deems them significant. If public history is a way of cultivating citizenship, then it matters which stories get to be told to which communities. Additionally, many of the authors argue for balancing the economic stimulation that often accompanies urban revival, with cultivating a sense of community. Too often, downtown areas get revitalized architecturally, only to have the people who lived there be driven out due to rising real estate prices. not surprisingly, it is often Black people and other people of color who bear the brunt of this displacement.

The texts on historic preservation have resonated with me in particular, not least because I actually got to experience a little hands-on historic preservation back in college. During my sophomore year, I took a seminar called “Lake Forest College as Cultural Landscape.” Over the course of the class, we studied different architectural styles within the history of college campuses, with our own college campus serving as the primary case study. A significant assignment entailed doing a survey on a specific building. This meant that we needed to look at a specific building on campus and visually document all of its architectural features. We then needed to go to the college archives, do research on the buildings, and document what kinds of changes took place.

I was assigned a building called Moore Hall, one of the older surviving dormitories on campus. Built around 1892-1893 by the architects Pond & Pond, the dorm was originally intended as a second-class dorm for male college students. In other words, it was nice, but not quite as elaborate as a first-class building. Originally the structure was three stories high, but after a fire during the 1920s, it was rebuilt with a fourth story, because by that point the college was experiencing a housing shortage and needed more room. Over the next several decades, the building would undergo subsequent changes that gradually stripped away its original features. As a result, by the time I was surveying it in the early 2000s, a lot of the architectural features that made the building distinctive to its period, the qualities that we call architectural integrity, were gone. Moore Hall had also developed a somewhat infamous reputation as one of the least desirable dormitories, offering very little in the way of modern amenities. A few years after I took that class, the building was demolished to make way for a more modern, suite-style dormitory.

It was a very interesting project, but if I were to do it again, I would pay more attention to the histories of the people who actually lived in that dormitory. The main thing I remember about Moore Hall was that the jazz musician Bix Beiderbecke once lived there as a student, but I don’t recall all that much about the demographics of the building. What were the demographics of the Moore Hall community, and did that change over the years? How did people actually live in the building? What sorts of spaces did they use for social activities, if at all? In other words, I was so preoccupied with documenting the architectural history of the building, that I neglected its social histories, which were just as important.

It’s important to delve into the social histories because neglecting them can lead to real consequences in terms of living spaces. During that same seminar, we took several field trips to different college campuses in the Chicagoland area to explore other case studies that we could compare and contrast with the Lake Forest campus. One of these places was IIT, and more specifically one of its most famous buildings, Crown Hall by Mies Van der Rohe. Initially affiliated with the Bauhaus, he relocated to the United States and became one of the most important proponents of the International Style. He settled in Chicago, so a lot of his most famous buildings are in the city. I’ll admit, it was very cool being able to see this structure after learning about it in class.

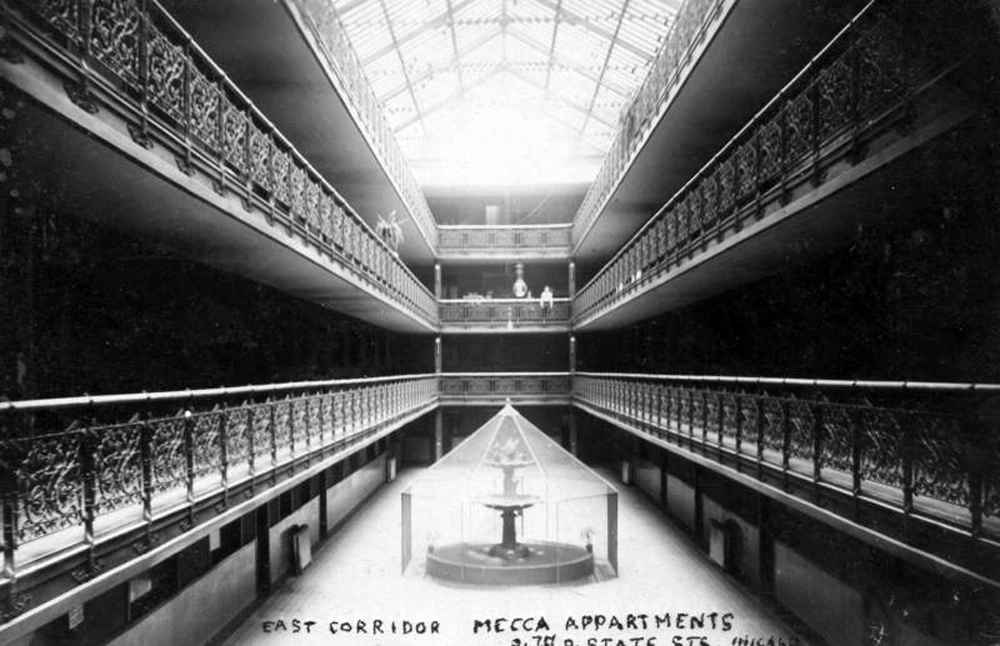

What I did not know about was the history of this site before Crown Hall, something I only learned about recently while reading “Mecca Flats Blues,” one of the essays in Giving Preservation a History. Before Crown Hall, there used to be an apartment building called Mecca Flats. Built in 1892, it served as a hotel during the Columbian Exposition of 1893. A distinguishing feature of Mecca Flats was its open-air lobby, which provided access to a communal space from the individual apartments. After the fair, it became a working-class apartment building. By the 1920s, African Americans primarily inhabited the building, and it was an important site for jazz and other kinds of performance. During the mid-twentieth century, IIT decided to take over this area in order to build a new campus in the International Style. Despite being an important living space for the African American community, as well as architecturally significant due to its distinctive lobby and multiunit living accommodation, Mecca Flats was ultimately cleared out and demolished.

If we ever discussed this history in class, I don’t remember it, which suggests that we didn’t discuss it nearly enough. If I were to take this college class again, I would hope that we would discuss this. Better yet, if I were to design a course like this, I would be sure to include this history and others like it.

Studying this history matters because we continue to live with its repercussions. If we don’t contextualize current living conditions within historical frameworks, and see how past actions have enabled present inequalities, it becomes tempting to look at the past through the lens of nostalgia. We wish for a sanitized version of yesteryear that never existed.

Contextualizing our histories is also important for accountability, something I’ve been considering with regard to the Northeast’s role in promoting systemic racial inequality. I’ve been thinking about this in relation to my very first museum job. During the summers of 2006 and 2007, I served as a tour guide for the Victoria Mansion in Portland, Maine. Built between 1858 and 1860, the house is an architectural gem, as it represents the earliest and most complete interior design commission for the Herter brothers, important American designers. Constructed in brownstone and emulating the Italianate style then popular in Europe, the house is a marvel, with more than 90% of its original interior features and furnishings intact (they’ve also been doing a lot of conservation since I worked there, so it looks even more spectacular now). When I gave tours of this house, I would talk about these features, from the symbolism of the paintings, to the hotel-like layout from which the homeowner, Ruggles Sylvester Morse, took inspiration.

What was only mentioned in passing was the house’s connection to slavery. Though originally from Maine, Morse was a hotelier based in New Orleans; the Portland house was his summer home. As far as I can recall he didn’t own any enslaved people himself, but as a businessman based in the South, his work benefitted from slavery as an institution. During the Civil War, he actually spent little time in New England because he was a southern sympathizer. While we would mention Morse’s southern sympathies during the tour, it was never a primary focus. Thinking back on the readings I’ve been doing, I wonder now what a tour centered on Morris’s role as a southern sympathizer and hotelier benefiting from slavery would look like. No doubt, the tour format has changed since I was a guide there, but if I ever revisit Victoria Mansion, I’d be curious to see what kind of content they address now.

The readings have especially resonated with me this time because so many of them connect to previous experiences, both as a college student and early career professional. While I cannot change the way these courses were taught or the way I conducted my tours then, moving forward, I can be more mindful of the kinds of issues these texts raise.

Great perspective and reference to work on campus buildings, Lake Forest. Moore Hall was built in 1892-93 as East House (Pond & Pond, architects), on land that formerly was a neighborhood of simple cabins for former slaves, ca. 1860s. So the new campus for LF Academy was an early “urban renewal” project. The African-American neighborhood of estate workers survived, though, south and west into the 1960s, with a few houses in the 1970s to 1990s owned by old families. Among the houses demolished was that of “Guv” Marshall, in 1879 the janitor for the Academy’s first 1859 frame building that burned with Marshall ringing the tower bell to warn the students. He is buried in LF Cemetery. LF College still owns three of the old neighborhood houses on the southwest portion of the block, near Washington and Illinois Rds. On the opposite corner was built in 1912 the Matthews stable, after the African-American couple sold their restaurant west of the train station to make way for The Market Square redevelopment of the LF downtown district, 1912-17.

Thanks so much for sharing your insights on the LF Academy campus and the African American presence in the Lake Forest community! Also thanks for the date correction for the old Moore Hall; I could always remember the architects but not the date. I’ll be sure to fix it. Your perspectives are always a welcome treat on this blog.