Last month I talked about my ongoing readings about the Uncanny Valley and other broad themes relating to robots. Today I’ll share what I’ve been up to since January 1st, and more specifically my explorations into the more nuanced aspects of human-robot interactions.

Most likely it’s my art historical background speaking, but I’ve been considering robots, particularly anthropomorphic ones, through the lens of spectacle. Since antiquity, after all, automata and other moving statues have been important displays of wealth and power among the aristocracy, with the movements of the machines themselves, as well as their sumptuous materials, suggesting their owners’ abilities to harness different natural and mechanical resources for their own amusement. Robots have also been an important source of spectacle throughout the 20th century. Just think about all the iconic robots that have manifested in film, from Maria’s evil counterpart in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, to the seeming indestructibility of The Terminator. Even more recent films like Ex Machina emphasize the sense of deceit and fraud we often attribute to robots, with Ava’s ultimate proof of her humanity manifesting through her willingness to lie and kill to ensure her survival.

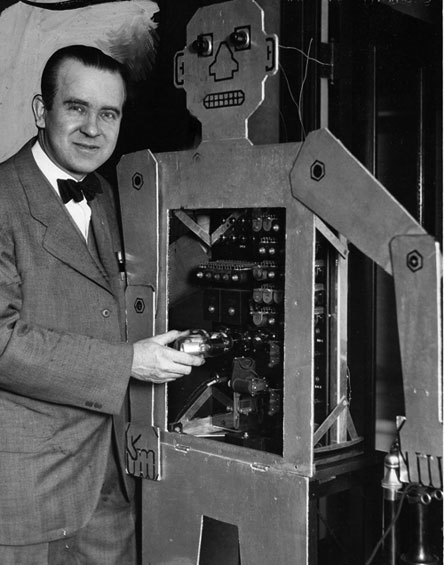

Nor are spectacular, anthropomorphic robots limited to fiction. Department stores featured electrical automata at the turn of the twentieth century, for instance, with electric power enabling them to run all day as opposed to a few minutes. During the first half of the twentieth century, many manufacturers created working robots for display at world’ s fairs, with the machines serving as potent and memorable advertisements. In 1927, Westinghouse created Herbert Televox. while Britain’s first robot, Eric, debuted at the Exibition of the Society of Model Engineers at London’s Royal Horticultural Hall in 1928. A replica of Eric now resides at the London Science Museum.

And then there’s Elektro, a 7-foot robot that could walk, talk, count, and even smoke thanks to a set of bellows, hearkening back to the smoking automata of the 19th century. He first appeared at the Westinghouse display for the New York World’s Fair in 1939, where he makes a memorable appearance in the film The Middleton Family at the New York World’s Fair. He proved so popular that he would reappear at the 1940 Fair with a robot dog named Sparko. Following World War II, he’d go on tour, and even appeared in the B-movie Sex Kittens Go To College with Mamie Van Doren. He now lives at the Mansfield Memorial Museum in Ohio.

All of these spectacular displays underscore both the anxiety and optimism we experience regarding robots. Examples such as evil Maria underscore the threatening presence we often attribute to robots, and their destructive potential regarding human society, whether through ensuing outright chaos, or rendering us obsolete. Conversely, robots such as Elektro, with humorous personalities and impressive but ultimately non-threatening counting or talking capabilities, suggest the potential for robots as helpers or companions, supplementing rather than supplanting human life. Both of these extremes position robots as the other. They act either for or against us, but rarely work with us.

Yet many contemporary artists have been exploring a third, collaborative option, and to me, this is some of the most interesting work out there right now with respect to robots. Instead of viewing these machines as existential threats or helpers lacking agency, some artists instead approach them as collaborators, and integrate robots into their artistic practice in order to expand the creative possibilities of their work. An early example includes Polish artist Edward Ihnatowicz’s work from the 1960s and 1970s, considered seminal in the field of cybernetics.

For a lot of artists though, it’s not just about programming robots to paint. Instead, they explore the creative potential of robots by forming meaningful collaborations that extend beyond simply programming the performance of rote tasks. Such inquiries delve into AI and its potential for both humans and robots regarding creative expression, as opposed to pessimistic, dystopian visions of human obsolescence or overly-simplistic presentations of robots as helpful servants. Artists such as Sougwen Chung and Pindar Van Arman both explore these ideas through their robot partnerships. Chung builds robots and then collaborates on painting-based performances with them, responding spontaneously and organically to the mark-making of the machines. Pindar van Arman, in turn, builds robots capable of making creative decisions via the use of neural networks and AI.

What all of these different forays underscore for me is the variety of emotional responses we experience to robots. Some of us may fear them, others may be merely curious, still others may be eager to work with them on new projects. Yet all of these responses deserve consideration.