Last month I shared some of the big ideas I’ve been thinking about regarding the dissertation. Today I’ll talk about how I’ve been exploring different topics within those bigger ideas to render them more manageable.

I started January’s work by taking a closer look at the idea of federal art funding. While attending an online webinar on Green New Deal posters, hosted by the Living New Deal, I learned about the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), a law enacted in the 1970s that benefitted artists on a national scale until its termination in the 1980s. Unlike the FAP, which was centrally operated through Washington offices, CETA was a decentralized program, with local cultural organizations deciding how best to use the money they received. Additionally, since the emphasis was on training as well as employment, many of these organizations required a service element, which meant that artists spent as much time teaching classes or providing public cultural enrichment as they did making art. Some organizations that benefitted from this funding include the Painted Bride Art Center and Brandywine Workshop and Archives, among many others. Compared to the FAP, CETA’s creative legacy is more difficult to trace because it emphasized service over making public art. Yet in a lot of ways it was arguablly more successful than the FAP because it provided a lot more agency to local communities in terms of assessing what they needed in terms of cultural enrichment. As an art historian, I also find CETA’s more obscure legacy indicative of the discipline’s bias toward objects, with the production and circulation of art objects receiving more scholarly attention than teaching efforts. I started thinking it could be interesting to compare the CACP with CETA-funded organizations to see how they interacted with their respective communities and whether they had any long-term impacts on their respective cultural landscapes.

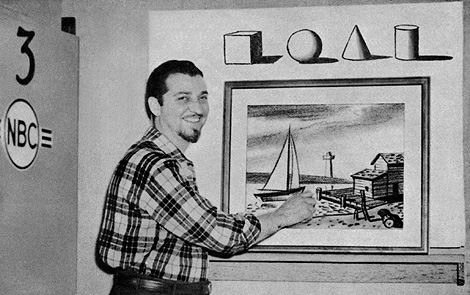

Then I started considering the more commercial aspects of art access by learning about televised art programs, the commodities associated with those programs, and correspondence schools. Before Bob Ross encouraged viewers to paint happy little trees, Jon Gnagy helped viewers tap into their creative side with a television program launched in the 1940s. Working in chalk rather than paint, he’d guide viewers through landscapes, genre scenes, and other subject matter while teaching them how the basic forms of spheres, rectangles, cones, and cylinders could enable them to draw any picture they’d like. He also sold his own drawing kits and books, and offered promotions for programs like the Famous Artists School, one of the art correspondence schools active during the mid-twentieth century. Founded by illustrators such as Norman Rockwell, correspondence schools would have students buy a series of classes. Students would mail in drawing assignments, and instructors would comment on them. These schools took a firmly commercial bent to their teaching philosophy, such as promising a rewarding career in illustration, and as such were derided by critics and educators (indeed, the intersections between democracy, capitalism, and ehat constitutes good art in American culture merits further exploration). Yet they’ve left an indelible mark on American art. Thousand of students received their first serious instruction through these programs, some of which, like Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, would go on to have seminal careers. Grant it, the vast majority of students didn’t transition into the professional art world, but the connection between correspondence schools and other commercial forms of art education and the art world merits deeper consideration.

Then I turned back to the idea of traveling exhibitions. Focusing on the twentieth century, I learned about initiatives that larger museums such as the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art explored during the 1930s and 1940s. In the case of the Art Institute, the museum launched an experimental extension gallery program in Garfield Park, with the museum regularly rotating works from the permanent collection. As Sylvia Rohr explains in an article on the Art Institute’s education history, the museum had explored opening other galleries, but ultimately shut down the program in 1938, possibly due to the Community Art Center Project already filling that role. Meanwhile, the Met, as Stephanie Post describes in a blog post, launched a traveling exhibition program focused on serving the different boroughs of New York City by sending exhibitions of materials from the permanent collection to area schools and libraries. This program ran until 1943 before closing due to its expense. Conveniently, the Met is currently doing a retrospective on this program as part of its 150th anniversary exhibition cycle, and if we ever get out of the pandemic I might go check it out. I’ve also been reading about artmobiles and other forms of portable exhibitions, including the VMFA’s own Artmobile, in action from the 1950s to the 1990s and recently revived in 2018.

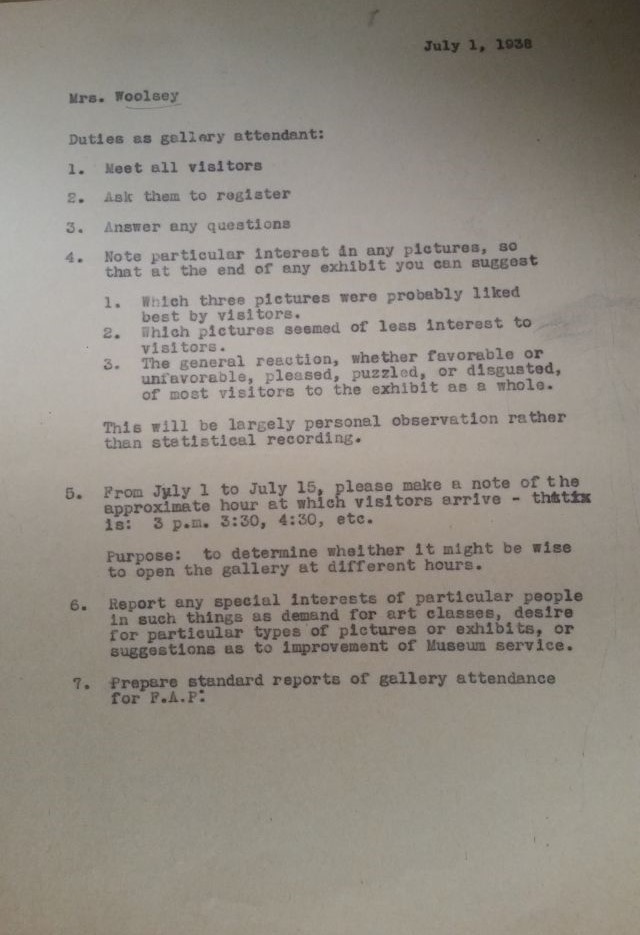

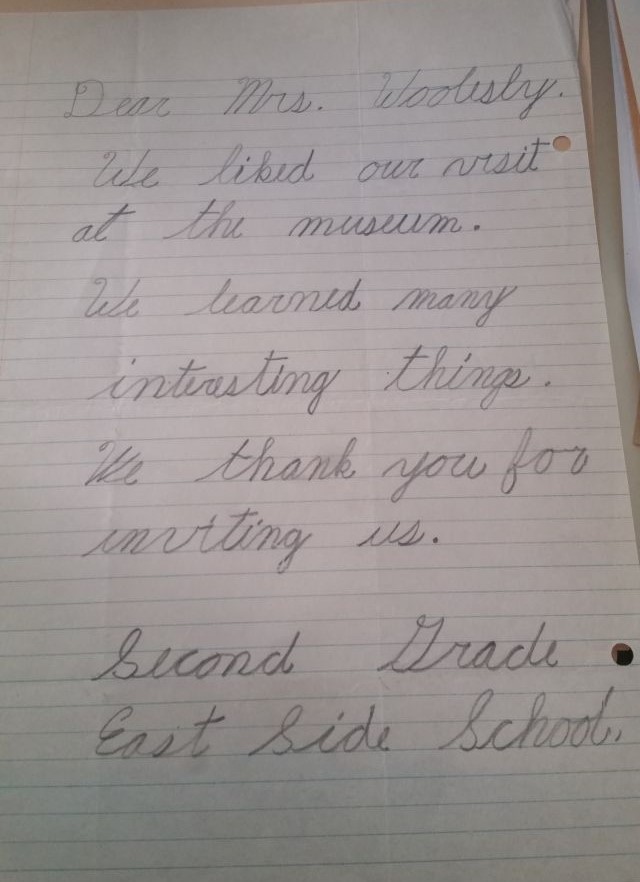

The most exciting facet has been the information I’ve been finding for federal community art centers. Over the past several weeks, I’ve been in conservation with several different museums that, like Roswell, were federal art centers at some point in their history. These include the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Middlesex County Museum in Saluda, Virginia, and the Greenville Museum of Art in North Carolina. While the Walker Art Center is currently closed to the public due to the pandemic, their wonderful archival staff has been helping me with questions and sharing online resources and finding aids. I’ve also been exploring the materials available at the Middlesex County Museum and Greenville Museum, and the materials I’ve been finding have been intriguing, especially when it comes to exhibitions. When I was looking through the Greenville materials, for example, I recognized several of the shows, from “The Making of a Mosaic,” to “The Industrial Scene,” as exhibitions that had been shown in Roswell, usually a year or two earlier. To me, it’s absolutely fascinating to know that audiences in New Mexico and North Carolina were seeing the same materials within the same few years. It makes me all the more eager to want to reconstruct the travel routes of these shows and get a better sense of the FAP’s mobility as rendered through the Exhibition Section.

From an archival standpoint, these institutions also raise important questions about what get saved, what doesn’t, and how that affects the historical narrative of each organization. Of the three archives I’ve seen in person, Middlesex was the most consistent in terms of keeping monthly reports, offering a good overview of museum activities. Greenville didn’t have the same monthly reports, but it did maintain exhibition schedules for all the North Carolina art centers, along with exhibition descriptions for each show, providing a more thorough overview of the circuit for that state. Roswell, on the other hand, has the most extensive correspondence, offering insight into not only what the museum was doing, but the challenges it encountered, from lack of money to technical difficulties to staff disagreements. Yet all three lean strongly toward the federal side of the community art center’s operation, with little to no primary documentation from the people who founded these institutions or the visitors who attended their exhibitions and programs, an omission that seems pretty glaring considering that these centers were designed to benefit these very populations. Indeed, just discussing the nature of these archives, and their collective assumption that these programs didn’t need local perspectives beyond newspaper write-ups to verify their efficacy, could be a chapter unto itself.

Traveling exhibitions are where I’m leaning the most right now. Not that these other topics won’t come into play, but in terms of focus, based on my own interests and experiences, this is where my questions are coalescing. Why? Because as a form of communication and art education I think they should be looked at more critically. There’s plenty of critique about blockbusters as profit-driven, vapid, entertainment-focused spectacles, but the ecosystem of traveling exhibits is far more complex and varied, with the big, attention-getting shows comprising only one aspect of what’s out there. There are exhibitions that museums put together and travel on their own, as well as exhibitions curated by organizations like the American Federation of Arts or Guest Curator, with museums as their primary clients. There are shows that travel to schools or libraries, and even shows that travel on their own bus. And then there are the shows that especially interest me: art exhibitions designed specifically for regions that don’t have their own museums.

Throughout these different forms, however, there’s an ongoing message about these exhibitions being inherently good. That by putting art on a bus or taking it to the local neighborhood (and providing free admission in the case of outreach exhibitions), museums and related cultural institutions are automatically doing a good thing for the communities they claim to serve. But what kinds of narratives are these traveling exhibitions espousing? Do they challenge the canon or reify it? Which neighborhoods within a county do they specifically visit? Do these communities have any say in what kind of art gets selected, or is the museum the one who decides? Finally, who performs the actual labor of implementing these exhibitions, and does their work get recognized?

These are the kinds of questions that I’ve been thinking about. The next step is to narrow down my potential case studies and assemble my proposal.