As promised in last week’s post, here’s my first update on my dissertation work for 2021. Since we’re covering what I’ve been up to since finishing comps, today’s post will be a bit longer.

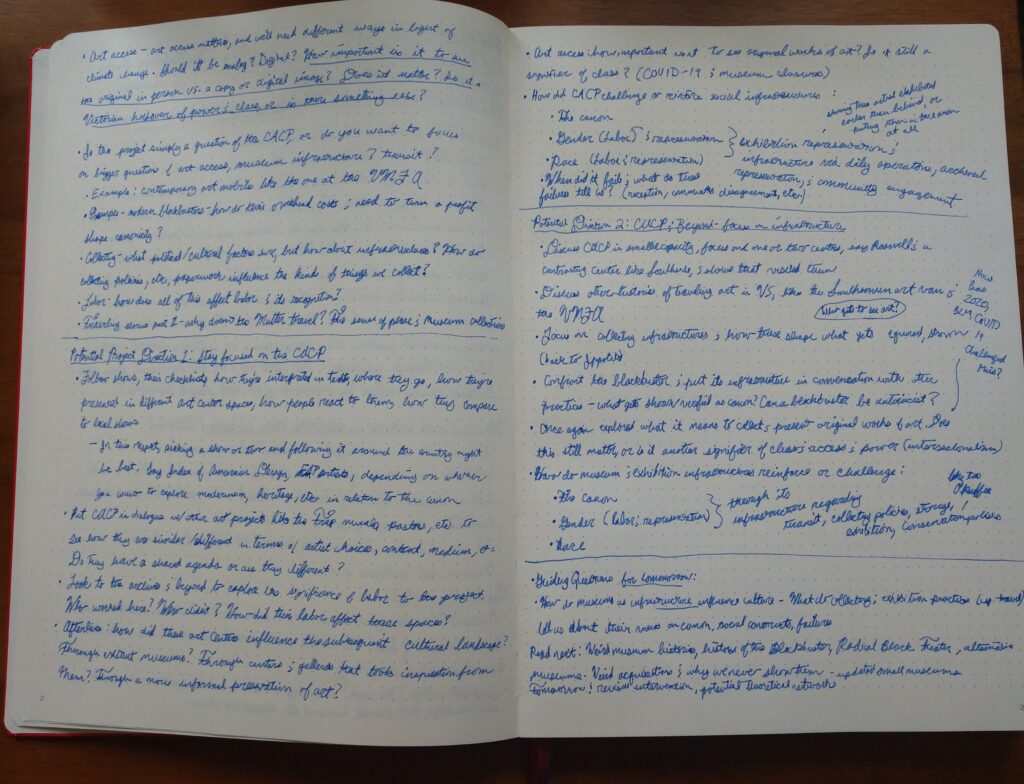

At this point, I’ve been doing more thinking than finished writing. While I do have a growing repository of free-write sessions and mock prospectus samples in my dissertation folder, the main thing I’ve been working on is figuring out what my core research interests actually are beyond whatever I find interesting within the context of a specific seminar or exhibition.

As I’ve mentioned since starting this blog, what I want to write about are federal community art centers, but what I’ve been trying to figure out since finishing comps is the context in which to write about them. After all, what’s the point in having a great research topic if you don’t have any engaging questions for it? So for the past few months, I’ve been thinking about what my framework actually is, and ultimately, what my core research interests are beyond any specific topic like the CACP.

This means that I’ve been reading about various subjects and discussing potential theoretical frameworks with the dissertation writing group I joined last fall. Given the connection between museums and art centers, I’ve been reading a lot of museum theory in terms of power relations and the way museums maintain the status quo through their collecting, exhibition, and labor practices. This has included classics such as Tony Bennett’s The Birth of the Museum, which draws heavily on Foucault, as well as more recent publications such as Joan Baldwin’s and Anne W. Ackerson’s Women in the Museum, which considers how museums both empower and constrict women through their professional cultures. As I mentioned in my previous post on SECAC, I’ve also been interested in cataloging and archival practices and how they shape the art canon, particularly through a lack of documentation or visibility.

From an archival standpoint, I also finally went through and organized some research I did on the Mildred Holzhauer Baker papers at the Archives of American Art, which I visited in the fall of 2019. Baker was the director of the FAP’s Exhibition Section and assembled all of the traveling exhibitions for the CACP (which, considering that the total was over 500 shows, is impressive at the very least), so she played a major role in the program’s educational trajectory. Since the CACP was a Depression-era project, I’ve also been perusing works that explore the material and visual culture of that time. Jani Scandura’s Down in the Dumps has been a particularly engaging read, given its somewhat personal approach to the archive, and its geographic variety in terms of case studies offers a model for my own work, as the CACP was not restricted to one specific state or region.

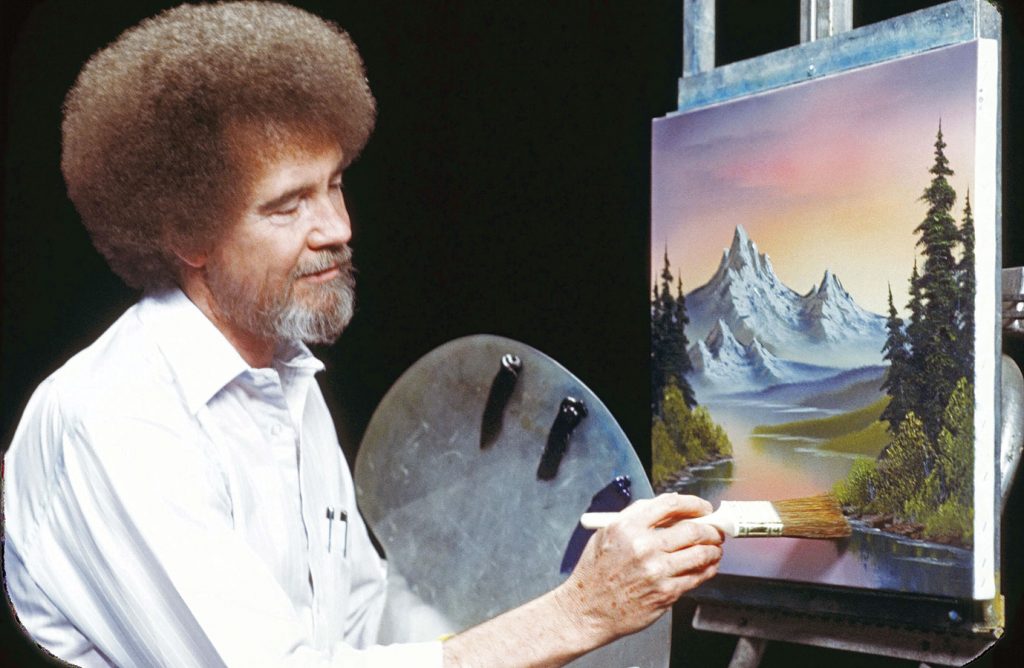

The other subject I’ve been reading into is art amateurism. Not necessarily folk art or outsider art, per se, but art made by nonprofessionals or people who didn’t get their training from the academy. So I’ve been reading about forums such as Etsy where people share or sell their work, celebrity art teachers such as Bob Ross and other icons of art populism, the paint-by-number fad of the 1950s, and even the emergence of chain art supply stores or mail-order suppliers like Michaels or Blick. What I’ve been focusing on is not so much what people actually make, but how they access the education and supplies needed to create this stuff.

What I’ve been learning from all this is that as a scholar, I’m interested in questions of art access, particularly for nonprofessional art practitioners. What engages me aren’t so much the careers and works of professional artists, the people associated with the art world as defined by curators, gallerists, and collectors, but rather than millions of people who make art without ever being recognized in a formal capacity. I’m not even talking about so-called outsider artists or folk artists, people who have been identified by specialists as being worthy of the canon due to what they consider their untainted creativity. I’m talking about the millions of people who, like me, make art but not professionally. Maybe they’ve taken a few classes; maybe they learned to draw from a book or watching tutorials. Maybe they even manage to make a living outside of the gallery circuit, whether through selling on Etsy or by the roadside. Or maybe they make pieces for their family and no one else.

This brings me back to the CACP. Initially, I became interested in this program because of its national travel infrastructures and the mobility underpinning its operations. As a curator who often transported exhibition materials myself, either in my own car or in a rented Uhaul, the idea of a national traveling exhibition program that brought art materials to different places by train really intrigued me. This still interests me, but it also ties back into the question of access, because what made this program unusual (to me at least) was that it catered to nonprofessionals. Unlike the workshops, murals, and other projects associated with the FAP, which hired professional artists, community art centers were designed with amateurs in mind. Sure, the staff who taught at them might be professionally-trained artists, but the students they imagined taking their classes, both adults and children, were not. Indeed, FAP administrators continually stressed that community art centers were not intended as professional schools, but as places where people could learn to appreciate the arts through looking and doing. And I think that’s worth exploring more deeply.

Why? First off, by focusing exclusively on artists who have been deemed worthy of the canon, we’re ignoring a lot of creative output. Maybe it’s not the most original or innovative material out there, or maybe it is, but so long as we only focus on the artists who show their works in museums or galleries, we’re always going to have a limited understanding of what people make when they envision themselves as artists. Second, taking a closer look at how people working outside of public schools or academies access art resources could help us better understand the state of art accessibility in the United States. We tend to lean on the narrative of art access being dismal in this country, but what if we’re using the wrongs metrics to gauge it? I’m not saying that formal art enrichment programs aren’t necessary or important, but they might be more effective if we study how different communities or individuals learn to make art without the benefit of a school or similar organization. This, in turn, leads to my third point: how museums can better engage their audiences. As ongoing critiques have pointed out, museums often uphold rather than challenge inequality and other social norms through the art they collect, the artists they show, and the classes they offer. What would happen if museums shifted their emphasis away from defining canonical art and instead focused on art-making as a creative practice performed by all members of a society, community, or culture? What would that look like?

These are all huge questions that go way beyond what any dissertation can cover, but thinking about these big-picture inquiries has helped me get a better understanding of what interests me as a scholar beyond the specificity of the CACP itself. The next step is to narrow this down to something manageable.

Admittedly, this has been a new experience for me. When you take classes in the semester format, you usually have to figure out your paper or project topics fairly early on so that you finish on time. Especially for someone like me who spends a lot of time revising my writing, this means going with the first or second idea. Similarly, when I was curating full-time, the logistical demands of the exhibition schedule meant that I had to pull together concepts fairly quickly so that there would be enough time to print labels, check artworks for conservation needs, prep galleries for installation, and so on. Even my undergraduate thesis had to be written within a year, so I only had a couple of months to nail down what I was going to write about. All of this is to say that my projects have generally emphasized results over ideas, so I’ve tended to spend little time in the conceptual phase.

In some ways, it’s been liberating. Over the last few months, I’ve had to start reframing my understanding of progress and to recognize that not every accomplishment can be measured by the number of words written or edited. Some days I write a lot; other days I go for long walks and talk out different ideas or scenarios with myself. Some days I research; other times I completely switch gears and work on my art. I’ll admit, I often feel like I don’t have much to show for all this thinking. Yet by giving myself the space to think through different ideas or scenarios, I’m ultimately coming up with a more innovative dissertation while discovering new topics and questions that will fuel my research for years to come.

At the same time, it’s been overwhelming. Over the past few months, I’ve probably imagined at least half a dozen potential iterations of the dissertation. Some versions concentrate solely on the New Deal era. Some versions are more focused on exhibition practices. Others look away from museums altogether and explore the commercial side of art accessibility through the expansion of chain supply stores. With so many different ways to approach the question of art access, it’s admittedly been a bit overwhelming to realize just how many ways I can go about answering it.

But the key is to remember that I don’t have to pursue all of these directions. On the contrary, I can’t, because the resulting tome would be far too long for anyone to want to read, let alone write. Not all of these potential directions interest me equally, so the next task is to figure out my focus. After all, the best dissertation is the finished one, the one that gets me my degree, and in that respect, the one that works for my needs is the one that I’ll actually want to write.

Besides, all these other ideas mean future book projects, right?

Interesting to see your process now that I’m a few years out and can look back at that time with greater clarity. Good luck narrowing down your topic!

Fwiw – I learned through my dissertation that the federal government has had underlying motives to distributing art and art education around the country. I discovered that a lot of the focus in the 1930s was to disseminate Latin American art and music specifically, so that Americans would come to appreciate our southern neighbors to some extent and they, being supposedly grateful for our attention, would then join the Allies for the war effort rather than the Axis powers (and creating another front on our own border). So you may want to look at the international political ramifications of these purportedly domestic social programs, as well. If any of that is of interest to you, let me know. Happy to share sources!

Hi Aubrey, great to hear from you, and thanks so much for your insights! I agree it’s definitely worth considering the international aspects of the FAP and other domestic programs, if only to remind readers that we’ve never been as isolated as we think we are. The U.S.’s interest in Latin America as a potential Ally sounds fascinating, so if you don’t mind sharing sources, feel free to send them along! In the meantime, I hope you’re doing well and staying safe.