In November I talked about a new exhibition I’m working on with the Barry Art Museum that looks at robots and automata. Today I’ll review what I’ve been up to since that initial post.

I made my first on-site visit to the Barry Art Museum (socially distanced and fully-masked) in early December. I went there to see the gallery I’d be working with, assess the exhibition furniture, and overall get a better sense of the museum as a collection and space. Since the Barry is a new institution, its furniture is in great shape and there are a lot of pedestals, movable walls, and other pieces available, which is really helpful since there will be a lot of three-dimensional objects in the show. The galleries are also well-lit, with Soraa bulbs (the brand the Roswell Museum used when it renovated its gallery lighting a couple of years ago) illuminating the spaces brightly and evenly but without overwhelming glare. Seeing the space in person also revealed some of the quirks of the gallery, as no exhibition space is perfect and there’s usually at least one peculiarity to work around. In the case of the Barry, one end of the gallery receives more natural light than the other, which is important to keep in mind with light-sensitive objects. All of this will be very good to know when it’s time to start laying out the show several months from now.

After that visit I began reading about some of the theoretical and philosophical concepts associated with robots and automata. One idea that pops up frequently with robots or any simulation of humanity is the Uncanny Valley, or that sense of unease we get when we see something that looks human but isn’t quite pulling it off, either due to the way it moves, the lack of animation in the eyes, or something else (for examples, see critiques of the movies The Polar Express or Cats). Masahiro Mori initially defined the concept in a 1970 article, but an English translation only became available in the early 2000s, so it’s become a lot more popular in recent years.

One of the reasons why I’ve been exploring these concepts is to find ways to connect the historical automata to not only the contemporary works that will be in the show, but also to the lives of visitors. Automata are objects we don’t often encounter regularly unless we either collect or build them, and the clothes they wear or the activities they do aren’t always immediately analogous to how we act today. I mean, how many of us would regard ourselves as fans of the Commedia dell’Arte, for instance, or enjoy the antics of clowns? If you love either or both, all the power to you, but I’d argue they’re not exactly mainstream the way the Marvel franchise is, for example. Yet even if these machines look strange to a lot of us now, or seem obsolete and old-fashioned, they remain relevant because they tap into a longer history regarding the tension between humanity and the mechanical other. Exploring how automata have encouraged people to think about changing technology, questions of humanity, and the weirdness of encountering machines that simulate us is something that we can connect to the 21st century, especially given ongoing concerns over robots as companions, caretakers, and workers.

More recently I’ve been alternating my reading material between historical automata and the work of contemporary artists interested in robotics. As historical objects, automata fascinate me because of how they embody change via class relations. Prior to the nineteenth century, automata were custom, hand-built creations. Often made in sumptuous materials such as precious metals, these objects were playthings of the extremely wealthy. By the nineteenth century, however, industrialization had enabled the mass production of clock parts and other materials needed for automata. As such, they could be produced in greater numbers, and started to be marketed to middle-class consumers looking for elegant, artful objects to decorate their drawing rooms. The activities these automata participated in, whether dressing up as stock theater characters or playing music, also reflect middle-class pastimes such as going to the theater or partaking in music. Automata embody a lot of other nineteenth-century realities too, such as colonialism, racialism, and expected gender roles, and I know I’ll need to address these issues.

In terms of contemporary artists, I’m keeping my options open-ended. In addition to looking up artists myself, I’ve also been seeing what kinds of robot-related shows other museums have been mounting for the past few years, both to get inspiration for my own show, and to see what I’d like to avoid. My greatest concern right now is to make sure that I don’t end up working exclusively with white artists. Robots, and more broadly the so-called hard sciences, tend to be associated with whiteness, both through popular media and the gatekeeping practices of the academy and other institutions. As long as I default to white artists, I will reinforce that expectation. Since one of the objectives of this exhibition is to attract new audiences to the museum, I want to make sure that white visitors aren’t the only ones who feel represented.

Fortunately, there are many BIPOC artists out there creating fascinating work. Stephanie Dinkins, for example, creates work that resists the whiteness associated with robots by rooting her technologies in Black narratives and experiences. In her ongoing piece Conversations with Bina48, Dinkins converses with an anthropomorphic robot about the race, gender, social equality, and how they intersect with other issues. In another work, Not the Only One, she endeavors to create a new kind of AI that draws on the multigenerational memories and experiences of a Black family, allowing the device to learn and narrate from people and sources that often don’t get represented in so-called traditional modes of AI and computer-driven work.

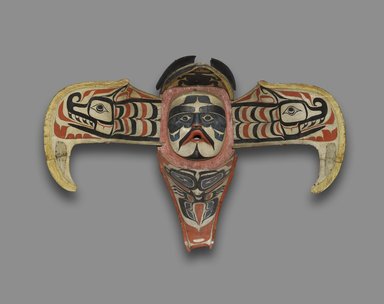

Right: Shawn Hunt, “Transformation Mask,” mixed media (2017, photo by Microsoft Vancouver, courtesy Audain Art Museum). See original image here: https://hyperallergic.com/436881/shawn-hunt-audain-art-museum/

I’ve also been looking at examples of robotics intersecting with Indigenous art. Transformation Mask by Heiltsuk artist Shawn Hunt explores transformation through a mask that synthesizes robotics, virtual reality, and Indigenous knowledge. The work takes inspiration from the transformation masks used among different Indigenous groups and cultures along the Northwest Coast, though it doesn’t copy or replicate any specific dance or ritual. Usually made from painted wood, these masks are equipped with strings that, when pulled, reveal a second face, an action that becomes a performance of transformation, such as from animal to human or from the physical world to the spiritual one. In Hunt’s Transformation Mask, 3D printing and other contemporary technologies are used in lieu of wood and paint, and instead of revealing a second mask, the wearers themselves become the mask, with the raven’s head opening to reveal their own face. Additionally, when the wearer puts on the mask, virtual reality lenses begin producing images that only they can see, enabling them to embark on their own visual journey. Through these intersections of Indigenous practices and technology, the wearer undergoes multiple transformations.

I still have a lot to learn and I’ve got a lot more work to do regarding representation. At this point, I’m not committed to any specific artists for show. Instead, I’m working on expanding my understanding of the variety of art, artists, and messages out there, and so far, it’s been an exciting experience. Aside from being a nice change of pace from my dissertation work, this project is allowing me to stay involved in the museum field while also learning about some fascinating new art.