For me, it was the typewriter.

A few months ago I was talking with Rose Eason, director of gallupARTS. It’s a nonprofit arts council focusing on the northwestern region of New Mexico. Aaron Wilder, the current curator at the Roswell Museum, introduced us.

GallupARTS is researching the history of the FAP in that part of the state, as part of a future online initiative. Since the city hosted an art center between 1939 and 1941, Eason has been exploring the Community Art Center Project, among other topics. Sharing notes has been great because she understands the program’s quirks and peculiarities.

During our most recent conversation, we compared letters that highlighted the contrasts between life in the 1930s and today. For Eason, the different causes attributed to various diseases stood out.

For me, it was the typewriter, or rather, the lack of one.

Recognizable, but also Different

Researching the CACP has taught me that the 1930s appear recognizably modern while being quite different from life today. Several scholars have identified the 1930s as the emergence of modern life as we know it. Susan Herbst does, for instance, in her study of mass media, A Troubled Birth: The 1930s and American Public Opinion. In photos, movies, and other visual media, the presence of cars, telephones, and other technologies can make life in that era seem relatable.

At the same time, my research on the CACP emphasizes the differences between life today and life then. That a nationally-reaching initiative like the CACP managed to operate without the Internet, for instance, still astounds me. I’m old enough to remember not having access to the Internet; I didn’t go online until well into middle school. Yet knowing that this program operated without the instantaneity of emails, texts, or Zoom calls impresses me.

For all the familiar technology mentioned in these documents, moreover, it’s their scarcity that most often stands out to me. Consider photography, for example. FAP administrators regularly requested directors of community art centers to send images of their sites to share with potential sponsors or supporters. Yet art center directors often emphasized the difficulty in obtaining photos of their sites. Usually, they cited the lack of available WPA photographers to visit them. Today, they’d probably use their phones to post videos of classes and other activities on TikTok.

Hidden Faces

I’ve been reading CACP documents for years. I’ve become familiar with the professional and personal dramas they discuss. Except for the top FAP administrators though, I don’t know what most of the people I’ve been reading about looked like. Take Martha Kennedy, for example. She was the first director of the Melrose Art Center, located east of Roswell. I know that she had mixed feelings about working there because she felt it pulled her away from her studio practice. Yet I don’t know what she or her art looked like. Or Ruth Covey. She felt insecure about her abilities as Interim Director at the Roswell Museum despite being assured she was doing a great job. I don’t know her appearance either. Even Roland Dickey, one of Roswell’s most active directors, I’ve only seen from a video made decades later, when he was well into his 80s.

At a time when visual culture seems more plentiful than ever, the CACP reminds me that abundance is always relative. What seems ubiquitous or omnipresent in one time period might appear spare from future perspectives.

Which brings me to the typewriter.

Typewriter Reflections

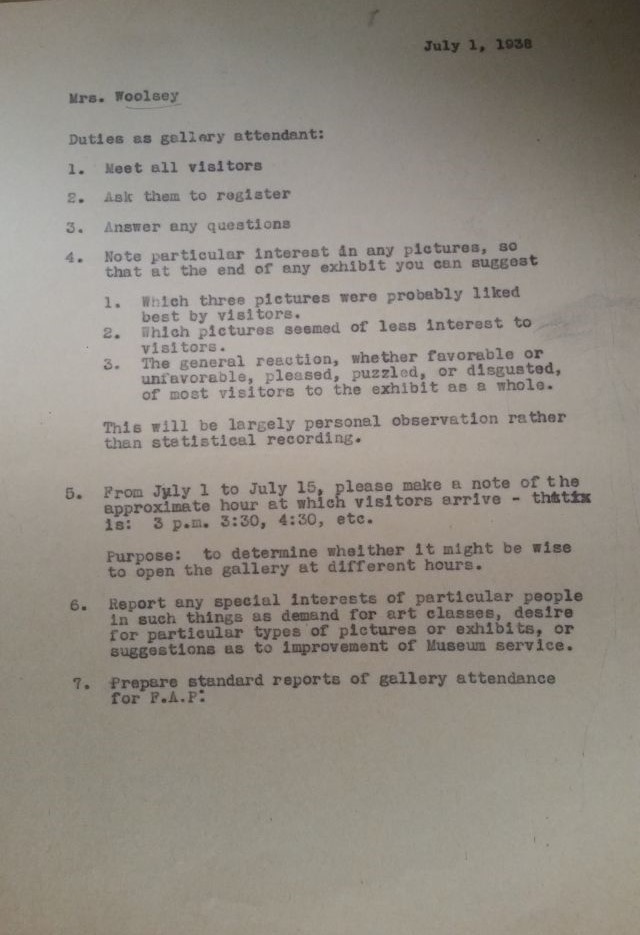

In the Roswell Museum archive, there’s a letter from Roland Dickey to Major Maurice Fulton, one of the sponsors of the Roswell Museum. Dickey provides a list of all the people who contributed to the building’s funding and construction. He also apologizes for not having the lists typed out. He hadn’t been able to complete that while they had a typewriter in the building.

Here’s a little context: as a WPA building, the Roswell Museum technically did not own a lot of its equipment. While the sponsors had paid for the actual structure, the WPA supplied a lot of its equipment and furnishings, from envelopes to typewriters. Due to restricted budgets and ongoing Depression-era scarcity, equipment sometimes rotated between different buildings. WPA administrators might loan typewriters to one site, and then allocate them somewhere else when the need arose.

That was what stood out to me. In my time (and taking into account privilege, etc.), laptops and other personal computers are required technology for students entering college. I’m typing this post on my laptop, a computer I can take wherever I need to write. When computers and their word processing software can be so abundant as to be mundane, not being able to access a typewriter because there simply aren’t enough to go around really stands out.

Thinking About Labor

Of course, the typewriter’s availability wasn’t all that struck me. I also started thinking about the specialized labor needed to work on it. Aside from the occasional poet, you rarely see typewriters in action anymore. Even in the 30s though, typing was not necessarily a universal skill. Throughout the archives of the Roswell Museum and other art centers, directors and other administrators request typists and stenographers, citing their voluminous correspondence as their primary reason. They needed people who had been trained to use typewriters and stenographer machines. The people who filled these roles were usually women.

As I read through these requests, I thought about changing work patterns. I’m not brilliant at it, but I type all my own documents, including this post. By contrast, women often typed the letters of art center directors and other administrators, either from dictation or handwritten notes. These women had often gone to special schools to learn how to type. Their skills were invaluable to ensuring the program’s constant, ongoing communication.

Bigger Reflections

As I reflected on the CACP’s archival record, I considered how women and their labor facilitated my own work. The Community Art Center Project can be a nebulous initiative to research, but one thing I appreciate is the legibility of its documents. To be clear, I can read and have read handwritten documents countless times. Yet knowing that much of the CACP correspondence is typed has made this program less intimidating to research. I know its documents will be readily legible more often than not. Women and their typing produced that legibility.

It reminded me of “My Mother Was a Computer,” a symposium I attended during my first year at William & Mary. Throughout the day, scholars highlighted how women completed a lot of work in transcription, calculation, and other quantitative tasks now carried out by machines. Early computing was possible because women completed the tedious labor needed to enable it. Similarly, the CACP’s archive became more accessible to me because of the women who typed out the thousands of pages of requests, complaints, and praise that circulated through the program.

My ruminations then recalled a lecture by Kay Wells. In her talk, she argued for the Index of American Design as an early example of digital humanities, both through the thousands of watercolor renderings of historical artifacts it produced, and the supplementary paperwork created to document them. The women taking dictation from Roland Dickey, Russell Vernon Hunter, and the other FAP staff wouldn’t have conceptualized their work as a digital humanities project. Yet in many ways, they anticipated the transcription and digitization happening now, to render documents more accessible. For me, their labor was a gateway into research.

Beyond the Typewriter

These are the sorts of rabbit holes you can fall into while thinking about your research. An apology for not providing a typewritten list leads to ruminations on technology access, women’s labor, and the digital humanities. Maybe this reflection will become an article, maybe not, but this is the kind of magic that can happen when you let yourself stop and think about what you’ve been learning.

What details from our lives will attract the meandering attention of future historians?