Art was always one of my favorite classes in elementary school. Compared to the rote memorization of multiplication tables or spellings words, drawing was a pleasant, creative diversion. I also remember the art teacher being a very nice lady who encouraged everyone’s work. She had long hair and wore long, flowy dresses or shawls with a vaguely New Age vibe.

My sole unpleasant experience with elementary school art occurred around the third grade, when this New Agey teacher asked me to change a landscape I’d been working on. The subject was a dog chasing after a duck that had just been shot. In all honesty, it was probably inspired by watching my sister and her friends play Duck Hunt.

The teacher didn’t like it because she thought it wasn’t nice. She believed children my age should draw happy pictures of trees or puppies, not ducks getting shot. I changed it, but was always a little chagrined about it afterward. I wasn’t an especially morbid kid; I just knew nature could be dangerous. I’d seen enough dead deer hanging off of people’s porches during hunting season, and seen enough documentaries about crocodiles hunting wildebeest, to know that nature isn’t always nice. Heck, my favorite Disney movie at the time, Fantasia, featured all kinds of hunting in its Rite of Spring segment, most famously with a T-Rex throttling a Stegosaurus (and yes, I know they lived millions of years apart, but it looks cool). I knew that hunting was as integral to nature as blooming flowers or hatching ducklings, and thought it should be rendered as such.

Perhaps that chagrin was one of the reasons why, many years later as a curatorial fellow at Shelburne Museum, I was immediately drawn to this painting:

This is Seal and Polar, painted around 1877 by Massachusetts-based artist Charles Sidney Raleigh. Originally an English seaman, Raleigh had a mid-life career change when he decided to become an artist and settled in Massachusetts. Self-taught, he painted signs, murals, and other projects. Of all his paintings, however, this one stood out to me. I’d seen plenty of Victorian paintings of animals hunting, Landseer being one of the more famous examples, but these were academic paintings, highly refined in execution. Seal and Polar Bear, by contrast, almost appears gleeful in its rendering, not unlike children when they play with their dinosaurs. The bear almost seems to be grinning as it raises its paw for a fatal blow, but that snarling seal, teeth bared, is also a dangerous hunter, the red of its mouth echoing the blood oozing from its tail. With its abstracted animals and almost cartoonish rendering of Arctic violence, I found it an engaging work of folk art and made it the centerpiece of an exhibition I was working on at the time, How Extraordinary! Travel, Novelty, and Time.

That exhibition would only be the beginning of my ongoing, meandering adventure with Seal and Polar bear as an image though. While I was researching the painting for the show, I learned that Raleigh painted at least two other versions.

The first was The Law of the Wild, from 1881, at the National Gallery in DC:

Compositionally it’s similar to the Shelburne version, though it could probably use a cleaning at some point.

The other was Seal and Polar Bear from 1886, on view at the Bourne Historical Society.

This is the grimmest of the three. The polar bear isn’t grinning anymore, and the ice floes have become more jagged and detailed, underscoring the harshness of the surroundings. The ship that was in the background of the other two works is also gone, further emphasizing the isolation of these two predators.

How Extraordinary! came and went, but Seal and Polar Bear always remained in the back of my mind. Why did Raleigh paint so many versions, and where did he get the idea to paint it in the first place? I knew from his biography that he never ventured to the Arctic, so I started wondering whether there was an image that Raleigh and seen and decided to reinterpret.

The magic of living in the Internet Age is that more material on every topic is always becoming available. Over the years then, I’ve casually done some online research on Seal and Polar Bear, and each time I do, I find more material on it.

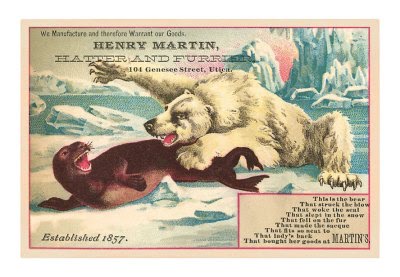

First I found these business cards around 2013:

Victorian businesses, along with individuals, often used calling cards to help circulate their name among consumers. Many of these cards included illustrations, often associated with the goods purveyed. The best-known or wealthiest companies usually often commissioned their own images, but smaller businesses could have their name and address printed on blank, generic images. Sometimes these images reflected their products, but a lot of the time they were based on pop culture.

Such was the case with these two calling cards featuring the very same seal and polar bear image. The top one is for a furrier based in Utica, New York, while the second one is a Boston company that specialized in hair products. I don’t know what hair products have to do with polar bears, but Victorians were fascinated with polar exploration, so it was floating around in the visual ether.

Perhaps Raleigh saw one of these business cards and decided to do his own painterly interpretation. Considering that they were in circulation in Boston as well as New York, if not other places, it’s entirely possible. I always suspected there was another image behind the calling cards, however, so I continued looking around.

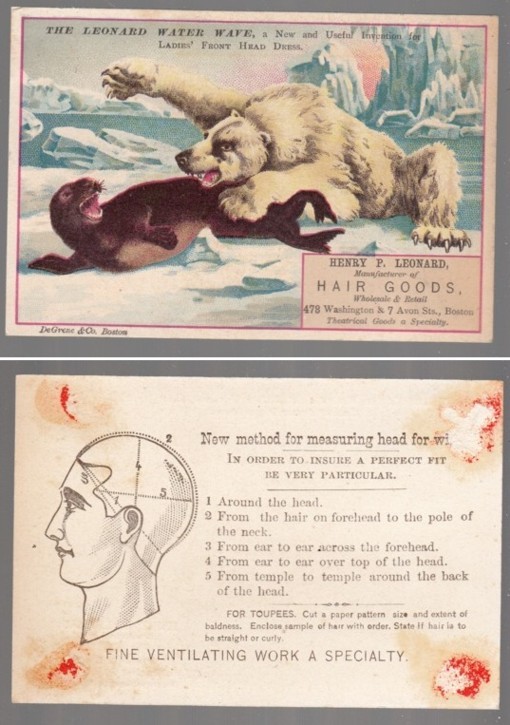

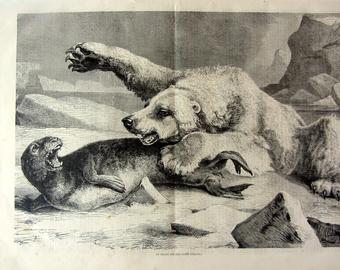

I made my next break around 2016, when I found this wood engraving for sale on Etsy.

Now I felt like I was getting somewhere. This print was much more detailed than the Raleigh paintings or the calling cards, and had the look and feel of an academic painting. It turns out it was a page from a French magazine that specialized in hunting. Still, a couple of things still needled at me. As a wood engraving, the print was likely based on yet another drawing and sketch: who could have done that? As a magazine that circulated primarily in Europe, moreover, it seemed unlikely, though not impossible, for Raleigh to have seen it. I wondered, however, whether it might have appeared in more than one publication.

Which brings us to 2019, when I found this image on Ebay:

Here we are again, with another wood engraving of Seal and Polar Bear, but this time it’s a page from an American publication, Harper’s Weekly. A little online searching revealed that it appeared in the July 1, 1871 edition. The caption underneath the prints reads “A Polar Bear Catching A Seal On the Ice,” and what’s more, it’s based on a drawing from Ludwig Beckmann. A little more searching told me that Beckmann was an animalier based in Germany, which would explain the more academic look of the drawing in comparison to the Raleigh paintings. Whether this was in turn based on observation or yet another source is yet to be determined, but that’s what keeps the journey going, right?

So here’s what I imagine: Beckmann does the sketch, which is turned into a wood engraving. From there it appears in different periodicals such as Harper’s. Somebody sees the print and adapts it into a business card. Meanwhile. Raleigh sees the business card or the print, and does his own interpretation.

And that’s the emphasis, interpretation. Raleigh didn’t copy the image, but added his own artistic license to each painting. From the abstraction of the animals to the changing treatment of the ice floes, what we have is an artist taking inspiration from the visual culture around him, and reinterpreting it through his own brush.

I don’t know what I’ll do with these findings in the long term, maybe they’ll become a conference paper or an article in the future, but if nothing else, Seal and Polar Bear remains as intriguing as ever.

And if I ever run into that art teacher again, I’ll be sure to introduce her to these paintings.