Every semester is different. I spent last semester working on projects relating to my work with the Roswell Museum archive, but this time I’ve been focusing on reading a variety of books relating to my more general interests, particularly the history of museums. As a scholar, I’m keen on connecting my practical experiences as a curator to my scholarly work, as I believe it enables me to examine the history of museums and related institutions from different perspectives.

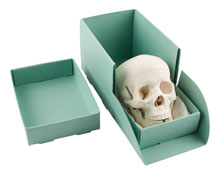

I found myself thinking about my previous experiences when reading Bone Rooms, which looks at the history of human remains in museums. While I’ve never worked at a museum with human remains in its collections, its stories about collectors did resonate with me, more specifically the anonymous ones.

When it comes to collectors in America, we tend to concentrate on the big names: JP Morgan, Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Havemeyer. Visit major museums such as the Met or the MFA in Boston and you’ll find their names all over exhibit labels and galleries. Museums such as Shelburne in Vermont or the Gardner in Boston were instigated by wealthy, eccentric collectors. Even Roswell Museum owes most of its collection to a handful of powerful collectors and philanthropists, most notably Donald B. Anderson.

Just as I tend not to focus on major artists, however, I found myself wondering about donors of more modest means while reading Bone Rooms. According to author Samuel Redman, numerous amateur collectors sent in human remains to museums during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were not wealthy or powerful, and today remain largely anonymous, yet they contributed substantially to these collections, and as a

From there, I started thinking about my own experiences with donors. With one or two exceptions, I’ve rarely dealt with significant donors. More often, I’ve handled phone calls and inquiries from people of more modest means, often folks cleaning out their parent’s attics or downsizing their own homes. They’re not extensive collectors, but people who happen to have objects they consider interesting or worthy of preservation, whether it’s a quilt, a painting, or even a bar of soap.

I then started asking myself questions about these donors. Who were these people

The one feature that stands out to me is narrative. When I think of all the prospective donations I’ve handled, the would-be donor had a story to share. Sometimes the object in question belonged to a

This emphasis on narrative and sharing underscores the significance of objects to memory, whether individual or collective. While museums have certainly elevated the sacrality of objects, their importance is underscored in other ways as well, with one of the most formative in my opinion being show-and-tell (speaking of which, is there a book on that?)

https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/books/show-and-tell-day-by-anne-rockwell/

As Peter Trentmann observed in his massive book, Empire of Things, people often express and articulate their personalities through the acquisition and consumption of things, so ascribing such importance to objects is perhaps not surprising. Especially when we consider the transient nature of our own bodies, knowing that our things will outlive us is comforting. They become contact relics, enabling us to connect with those who have gone while providing a link to future generations.

As repositories of objects, perhaps it only makes sense then, that these would-be donors would reach out to us. Who else would be better qualified to preserve the stories behind objects than a museum?

One thing is for certain: if a study hasn’t been done on non-elite donors, it should be. And perhaps I’ll do it.