Longtime readers of this blog know that the Roswell Museum and its archive constitute an important part of my research. After all, going through the Roswell archives was what initially got me interested in the Community Art Center Project. It also remains one of the most extensive and intact archival repositories I’ve encountered for an individual art center. Its contents span years of exhibitions, classes, correspondence, and more.

As significant as Roswell is to my work, however, there’s another art center that’s long intrigued me. Also located in New Mexico, this site served one of the smallest communities in the program, with its town population consisting only of 600 people. Despite its small community size, it became an exceptionally active and well-received center, attracting national as well as local attention. That success proved short-lived, with the site closing within a few years of its inauguration. Yet its memory persists in the archival record. Though it has no repository of its own (that I know of), it regularly crops up in archival collections spanning from Roswell to Washington, DC. It may be gone, but its archival traces refuse to be forgotten.

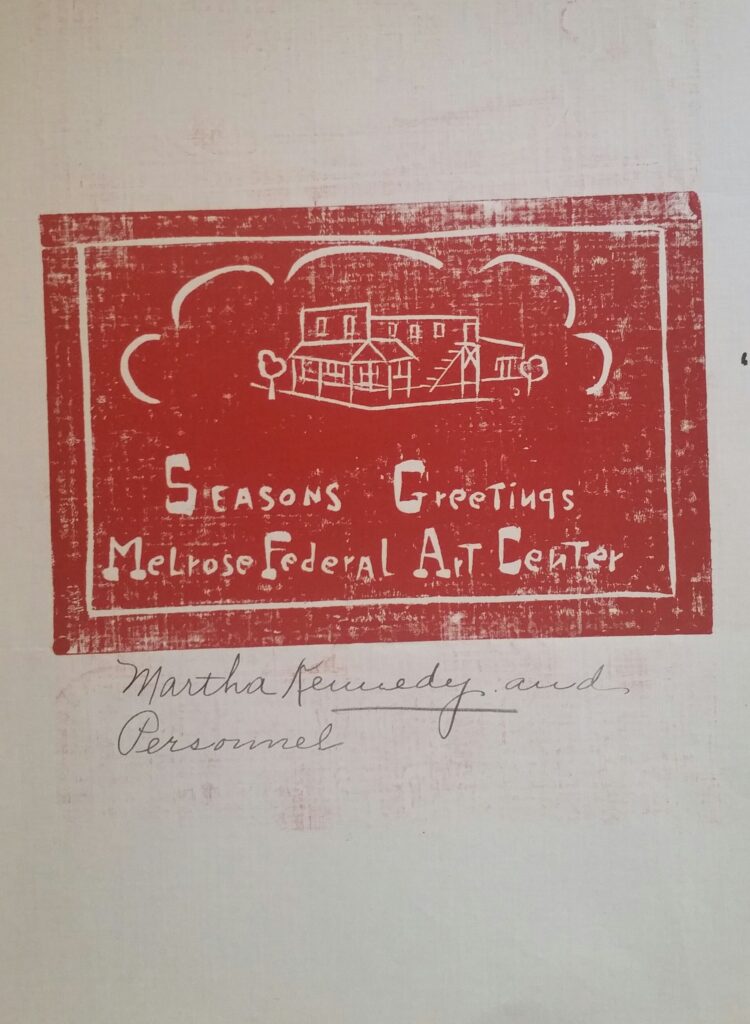

Today, then, I’d like to talk about this lost art center. Let’s take a look at Roswell’s neighbor, collaborator, and occasional rival: the Melrose Art Center.

About Melrose, New Mexico

Before we get to the art center, let’s begin with its site. Melrose is a village located in southeastern New Mexico. By car, it’s about an hour and a half northeast of Roswell, and a half hour west of Clovis. It’s arguably most famous as the birthplace of William Hanna (1910-2001), co-founder of the animation studio Hanna-Barbera.

Melrose’s population has always been small. In 1920, fewer than 370 people lived there. At its most populous in 1940, Melrose still had fewer than 1,000 residents, with about 850 people based there. Today, the population hovers around 600, much as it did when its art center opened. Like a lot of towns in New Mexico, Melrose is small, rural, and poor.

I never visited Melrose while I lived in New Mexico. Between my other professional commitments, I never got around to it. I considered driving there during my last trip to Roswell, but I only had enough time to finish my archival work before flying out again.

Although I’ve never seen Melrose in person, I have explored it online. On more than one occasion, I’ve gone on Google Maps to tour its streets. I wanted to see if I could spot the original art center building. Not surprisingly, I couldn’t find it, as it was likely demolished decades ago.

An Art Center Begins

The Melrose Art Center opened in 1938, a few months after Roswell’s. The FAP originally intended it to be an extension gallery of the San Miguel Art Center, located in Las Vegas. Extension galleries were small sites affiliated with larger art centers, and focused on rotating exhibitions. The community’s reception to the new Melrose site proved so enthusiastic, however, that it became a full art center in its own right, hosting classes as well as exhibitions. Within a few months, its activities eclipsed those of San Miguel altogether, which eventually closed in 1939.

Like many art centers, Melrose had a small staff. Its first director was Martha Kennedy, a Roswell artist who relocated to Melrose to run the center. Melrose was also typical of community art centers in that it initially occupied a renovated building rather than a new one. In this instance, its first home appears to have been an old store

The Melrose Art Center

From its inception, Melrose was a highly active site. Like Roswell, it featured handcrafted wooden furniture designed by Domingo Tejada, who transferred there to construct pieces for them. It also oversaw the creation of embroidered chairs and a hooked rug for the Roswell Museum stage. Its classes served residents in Melrose and its neighboring communities, and the reception appears to have been enthusiastic. One student, Roland Saxton, purportedly walked twelve miles twice a week just to take classes there. Melrose attracted both local and national attention, with FAP administrators in DC commenting on its robust activity despite its small size.

Melrose also had an active relationship with Roswell. Circulating exhibitions appearing in Roswell usually got shown at Melrose immediately before or afterward. Kennedy regularly shared her observations of audience reactions to shows with Roswell directors, helping them anticipate what kinds of responses to expect from their viewers. Roswell also experienced something of a friendly rivalry with Melrose, particularly since it experienced higher attendance numbers despite being a much smaller community. In an October 1938 letter, for example, Roland Dickey, Roswell’s second director, celebrates finally exceeding Melrose’s attendance numbers. As he admitted, it took a state fair and a teacher’s convention happening in town at the same time to do it.

1939 and After

Melrose’s archival record gets a bit hazy after 1939. From what I can tell, by the end of 1939, it had relocated to the town’s newly-completed City Hall, constructed through WPA funding. Although the space appears to have been smaller, the art center moved there due to ongoing heating issues in the original site. By 1940, Martha Kennedy had transferred to the Gallup Art Center. Although Kennedy appears to have been proud of her work at Melrose, she also seems relieved to have left. She observed in correspondence that its hectic exhibition and class schedule affected her ability to work on her own art.

After that, Melrose slowly disappears from the archival record. When Gallup closed in 1941, Melrose residents hoped that Kennedy would return, but that never happened. Following 1941, references to the Melrose Art Center disappear altogether.

Like many art centers, Melrose likely closed as a result of World War II. By the end of 1941, the only centers that continued to receive federal money were those refocusing their activities toward defense or serving military audiences. Roswell was one of these sites, given that it hosted the Roswell Army Air Field, later Walker Air Force Base. But for many art centers, funding dried up before they had the chance to establish their own long-term financial plans.

Melrose and the Archival Record

To my knowledge, the Melrose Art Center has no archival repository of its own. When I asked the Historical Society for Southeastern New Mexico whether they had any documentation on it, they couldn’t find any. Nor have I seen any collections dedicated to it exclusively at UNM or any other university holdings.

Yet I have found multiple references to Melrose in other archival repositories, including the National Archives and the Archives of American Art. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the most extensive records appear in the Roswell Museum’s archive. It’s got entire folders in its correspondence files dedicated to Melrose, while exhibition travel records indicate which shows traveled to the site. From Washington, DC, to Roswell, then, Melrose and its archival traces span the country. Its physical site may be gone, but in the archival record of institutions, at least, it’s not forgotten.

This interests me because it speaks to the connectivity of archives. So often when we visit an archive, we’re interested in a specific group of documents there. Yet archives do not exist in isolation, and their documents speak as much to the connections between collections and institutions as they do their own contents. Melrose’s cross-country record parallels the connectivity of the CACP. It may have served a village in southeast New Mexico, but it corresponded with its peers both in-state and beyond.

Future Plans

I’ve been thinking about doing something with Melrose for a while. Whether it’s an article focusing on New Mexico’s art centers, or the archival theory of Melrose as a vanished site, I think there’s potential to dig deeper. And who knows, perhaps one day I’ll finally visit Melrose to take in its sense of place.