Last week I finally completed a private commission for a family friend. I can’t show you the results yet though, because I don’t want the intended recipients to accidentally see it, so here’s a different post I wrote a few weeks back.

A couple months ago I saw a listing on the AAM website for a curator specializing in works on paper at the Dallas Museum of Art. Although I’m not actively applying for jobs right now, I periodically check listings to get a sense of where positions are cropping up and what kinds of skills or expertise they highlight. I also have a short list of museums I’ve been watching for years in terms of job availability, whether it’s because I like the collection, the location, or something else. I put the DMA on that list about a decade ago after interning there. I enjoyed working with the collection and had an equally great time exploring the Dallas/Fort Worth area, so I’d been open to going back if the right position opened up.

I first learned about this new works on paper position about a year before it became available, thanks to a post I’d read on the museum’s website. According to the museum, the gift included a substantial gift of prints and the funds to create an endowed position to curate it. I remembered thinking what a great opportunity it would be for whoever got it because they’d be setting the tone for the collection in terms of research, exhibitions, and future acquisitions. At the time I read that article, I planned on applying when it became available. I didn’t expect to get it, but I love curating works on paper and wanted to at least get my hat in the ring.

I should have been excited then, when I finally saw that position listed. As I read through the job description though, I didn’t find myself thinking about potential or opportunity. Instead, I remembered last winter, when the infrastructure supporting electricity to Dallas and other cities collapsed, leaving thousands of people without power for days or weeks at a time. Then I thought about the summer and the grid’s ongoing struggles to meet the needs for electricity and cooling. I imagined risking my well-being every summer and winter, with each season only getting more extreme. When I read through the listing, what I saw was a job that, for all its potential, wasn’t worth the risk. Instead of opportunity, I saw liability. So after waiting for than a year for this position to open, I scrolled past it without so much as looking at the application.

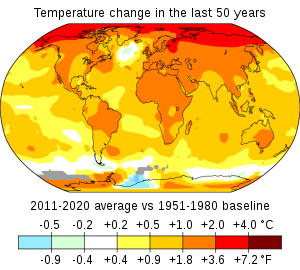

If you haven’t guessed, today’s post is about climate change, and more specifically, how it’s affected my life so far.

I’ve been aware of climate and our impact on it for most of my life. In elementary school, I watched a documentary in class where the narrator likened car exhaust to garbage being dumped in the sky. When my family moved from Maine to Arizona in 1996, one of the first things I learned about the state was that it was in a 30-year drought, and that supplying sufficient water was an ongoing issue. During middle school, I recall one of my teachers saying our current era should be remembered to future historians as The Age of Stupidity based on our treatment of the environment. I remember another staff member around that same time vehemently denying global warming. While doing research for a paper in high school, I remember getting infuriated when I learned that my then hometown of Prescott Valley, located in the high desert, had no fewer than four golf courses. It was also during high school that my parents started talking about selling their house and moving back to Maine before limited water supplies in the West depreciated their property value (they’d do exactly that in 2005, at the end of my freshman year of college). Years later, while working on the Magical and Real exhibition, I compared Peter Hurd’s childhood memories of Roswell with the city I knew, noting how much drier, hotter, and windier it had become over the past century (he also noted environmental changes within his lifetime, and lamented them). In Williamsburg, I worry whether there will be flooding whenever a tropical storm makes its way through the area, or whether water-logged trees will collapse on our building.

In short, climate change has been a part of my mental landscape for at least 20 years, whether people have been denying it, mitigating it, or anticipating future repercussions. And as such, it’s influenced how I’ve lived my life. I got my driver’s license at 16 but didn’t buy a car until I was 27, and that was only because I was moving to New Mexico, where there is no other reliable way to commute between the state’s various cities. Instead, I relied on foot power, car-sharing, and uneven access to public transit, things I still use whenever I can despite the inconvenience. I’ve gone years without buying new clothes beyond socks and underwear, and more often than not I opt for used ones when I do buy them. I limit my showers, turn off the lights when I leave a room, keep the heat and the air conditioning on the lower end to reduce energy use, and try to eat more plants. When we moved to our current place Brandon switched out the bulbs in the house with LEDs, and we’ve talked about getting solar panels whenever we buy a place of our own. As much as I love to travel, I feel obligated to limit my excursions. Climate change influenced my decision to not have children (though in all fairness it’s mainly because I’ve never wanted kids). I wouldn’t call myself a hardcore eco-warrior, but I’ve lived my entire adult life with an awareness of my environmental impact and a low-key guilt for existing.

Moving forward, I know that climate change will continue to shape my life. Whenever I look at jobs now, I pull up websites discussing how climate change will potentially affect the area where it’s located, and what kind of environmental disasters are likely to occur there. As much as I enjoy living here in Williamsburg, I suspect we’ll need to move further inland to avoid flooding, whether we stay in Virginia or go somewhere else. I wonder what it will be like to live in areas struggling to accommodate climate refugees, and how those migrations will continue to exacerbate inequality. I think about how my privilege enables me to consider avoiding disaster-prone regions. I’ve been fortunate so far in that I’ve never had my home or hometown destroyed by climate disaster, but I wonder when that will happen.

Why am I telling you any of this? Because I want you to know what it feels like to live with climate change on a day to day basis, even if it’s not necessarily impacting you directly. Being me in the era of climate change means feeling sadness because you realize that your world is getting smaller as more places become unsafe or uninhabitable. It means feeling angry at the politicians and corporations who foresaw this decades ago and opted for short-term gains over long-term responsibility, leaving the world to deal with the repercussions. It means grieving for the next generation because they’re going to have to live with this world and all its climatic extremes. It means constantly fighting off hopelessness (and the sneaking suspicion that the billionaires and politicians most capable of making lasting change are planning to flee into space or fancy underground bunkers) in order to press for change. Because the truth is, people are already suffering, already struggling, already losing everything, including their lives.

Despite what our nostalgia-prone culture may fervently wish for, we can’t go back to the climates we once knew. This is not just another anomalous El Niño year. We can’t undo the effects that are already happening. What we can do is keep them from getting worse, but we need to demand it as voters and consumers, because as long as the corporations doing the most harm still see profit in their current models, they’re not going to change. Why go through the effort of changing the status quo if you can still make money off of it?

Here’s a historical example to illustrate my point. In the nineteenth century, wallpaper manufacturers developed a vivid shade of green for their products. Green has always been one of the harder colors to capture in the pigment spectrum, so when they came out with this brilliant verdant hue, consumers absolutely loved it. Pretty soon, green wallpaper was everywhere, and it was printed with stunningly beautiful designs. The only trouble was, that vivacious green hue was achieved using arsenic. As the years went by, people couldn’t help but notice that they kept getting sick and dying in their homes. Doctors connected the dots and started calling out the arsenic wallpaper, recognizing that the poison could still affect you without being ingested. Touching it, breathing it in, that was enough to cause harm over time.

So arsenic wallpaper was a health hazard, one that had made people sick, and even killed older adults and children. But guess what? Wallpaper manufacturers continued to produce it because the demand was still there. Even though it was largely agreed that it was dangerous (although some proponents like William Morris expressed doubt) it continued to be sold because it still made money. It wasn’t until after consumers began demanding safe alternatives that manufacturers stopped carrying arsenic wallpaper. In essence, they only abandoned arsenic products when they became unprofitable. They didn’t stop making toxic green wallpaper for the good for the society, or even for the sake of the children. They stopped because there was no longer any money to be made in it (to learn more about arsenic wallpaper, check out Lucinda Hawksley’s book, Bitten by Witch Fever).

That’s where we’re at right now. We’re living in a house covered in arsenic wallpaper that’s already made us sick. And unless we tell our politicians, corporations, and ourselves that we don’t want to live in a house covered with toxic wallpaper, we’re going to die in it. In a capitalist society such as ours, everything, even our long-term sustainability on this planet, is evaluated through immediate profits. Because let’s be honest, it will take a lot of money and work to update that infrastructure. It will take a lot of mental and physical capital, resources corporations would rather not use if they can make money off of extant models. Unless we make it clear that there’s no alternative, the wheel will never be reinvented.

This is what I live with every day, and whether you acknowledge it or not, so do you. Climate change isn’t going anywhere, and the sooner we admit that and get to work, the better chance we have of not losing everything.