The past few weeks have been quite eventful in terms of Motion/Emotion, with the most salient development being the availability of new robots for the contemporary section.

Before I delve into those works though, let’s first review the overall organization of the show, which we settled on a few months ago. Part One will focus on the Barry’s automata collection. This is where we’ll provide historical context for them (this will be especially important for the Orientalist automata, which are problematic colonialist objects). We’ll also suggest how they connect to twenty-first century issues and concerns, from their influence on technologies such as the computer, to the overall way they embody ongoing fascinations with artificial intelligence.

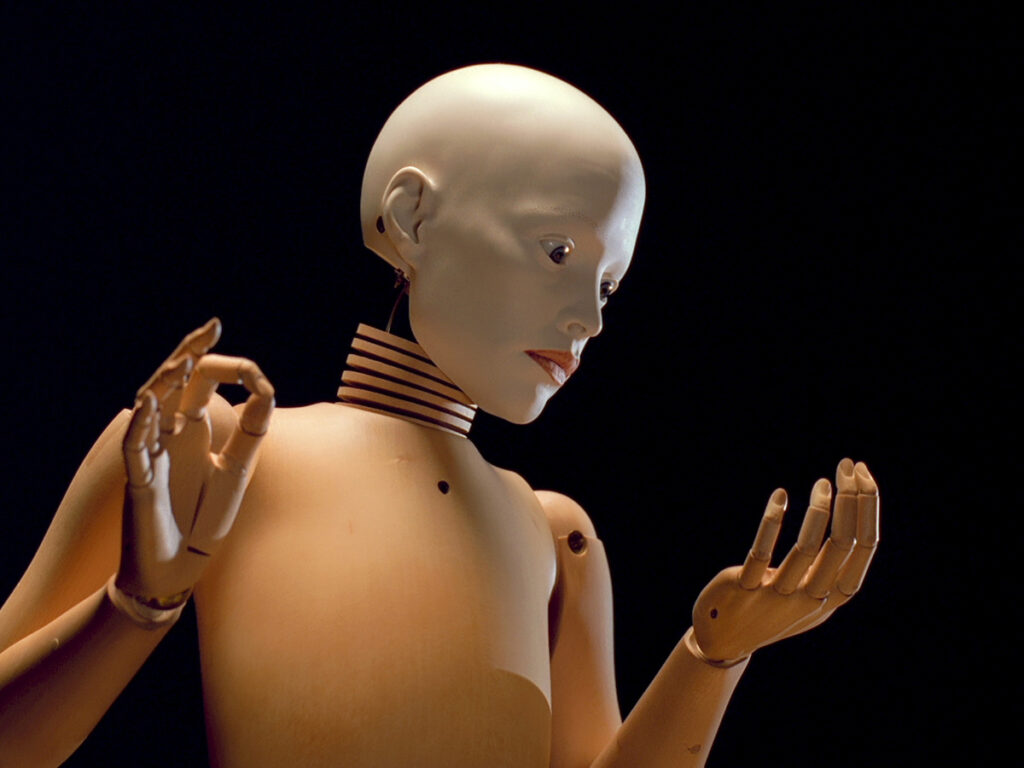

The second part of the show will then shift to a more contemporary lens by looking at the work of two artists, Elizabeth King and Joseph Morris. Both explore the idea of living in a body, but in different ways. We selected these two artists for both practical and thematic reasons. Although her works technically aren’t automata, King’s sculptures channel their appearance and movement with their articulated joints and meticulous details. The stop-motion animations she creates, in turn, offer an uncanny parallel to the movements of the automata while also underscoring the human presence needed to animate them in the first place, whether it’s through building the clockwork needed to move an automaton, or physically manipulating sculpture to make it appear animate.

Compared to Elizabeth King’s pieces, Morris’s kinetic sculptures are decidedly abstract, but they are nonetheless steeped in bodily experiences. Whereas King’s work overtly references the exterior of the human body, Morris evokes bodily processes such as respiration, with his breathing sculptures both exuding their own lived presence and encouraging viewers to think about the biological processes that enable their own existence. In different ways, then, Morris and King encourage viewers to think about the experience of living in a body. Within the space of the exhibition, these pieces also form a dialogue with the movements of the automata, with Morris’s pieces in particular offering a striking 21st-century response to breathing automata such as the Jockey Smoker, arguably one of the most uncanny automata in the collection.

Whereas this middle section of the show offers contemporary parallels to the automata through a largely artistic lens, the final part will focus more on STEM-related projects. We decided to bring a more overtly scientific and technological angle to the show for two reasons. One, we hoped it would bring new visitors to the museum by appealing to different interests. Second, we wanted to affirm the museum’s relationship with the university by featuring current ODU projects. We’ve already got the Advisory Board helping us with content and interpretation, but we also thought we should approach the gallery as an opportunity to showcase current research happening both on campus and in the greater Norfolk area.

And this is where the latest developments have been happening in terms of object selection. A few weeks ago we got in touch with another faculty member on campus who is heavily involved with robotics, both at the university and around the community. Through him, we’ve been invited to consider two different but intersecting robots. While they aren’t affiliated specifically with the ODU campus, they nonetheless emphasize the amount of robotic activity happening in this area.

Warning: the robots discussed in the remainder of this post address police violence and military firearms training.

The first robot is designed to train police in de-escalation techniques. Reflecting similar developments in medical training, the robot is intended to help officers recognize their racial biases in terms of civilian interaction, with its screen capable of being programmed to show different faces. The second is a target practice robot used to help military recruits learn to shoot accurately at long distances. In essence, one robot is meant to prevent violence; the other trains people to use it efficiently. So far I’ve only seen these pieces through photographs, but next month we’re scheduled to view them in-person.

In anticipation of this on-site visit, I’m focusing my current research on these two robots because they both address controversial subjects that demand tact and sensitivity. One of the most important things I’ve learned during my curatorial career is to recognize my own limitations, so in addition to doing my own reading, I’ve been reaching out to others to help me think about these pieces. I’ve been discussing these works with one of our Advisory Board members, for instance, because her own research focuses on the philosophy and ethics of robots. Given the ongoing controversy of the police and their tactics for apprehending civilians, particularly BIPOC civilians, I’ve also asked her to contact local criminal justice experts to help me address the question of the police in the Norfolk area. While the police robot is meant to de-escalate violence, I know that there have been contentious encounters with the police in this area, with some of the most significant being the protests that took place in Richmond last year.

The military robot is also a complicated object to think about. While the piece is an abstraction of a human body, the likelihood you’d accidentally mistake it for an actual person is pretty slim, it’s still recognizably human. More unnervingly, people are meant to shoot it. Regardless of how potential viewers feel about the military or guns, it’s a taboo object because it’s teaching users to kill people efficiently, something society generally tells us not to do. Depending on the viewer’s experience this could cause different responses, so I need to think about this piece carefully. Given their charged emotional content, both robots address ongoing themes within the show, but if we do include them, we need to be very mindful in terms of displaying and interpreting them.

So that’s where I’m at right now. These aren’t the only pieces potentially going in the contemporary showcase, far from it, but if they do appear, they will add a very serious tone to this section and should not be treated lightly.