As with last week’s post on my dissertation, today’s piece was done before traveling to Florida. Although we returned to Williamsburg yesterday, I didn’t want to make myself write a blog post right after getting back from vacation, so I wrote this is advance.

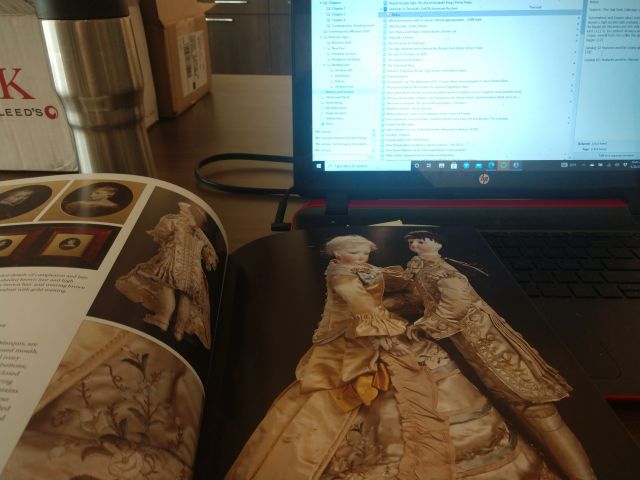

In addition to the automaton research I’ve been doing from home, I’ve started driving to the Barry Art Museum to peruse their library on dolls and automata, which their wonderful librarian and archivist put together for me. Compared to the primarily academic books I’ve been getting through William & Mary, many of these texts address automatons through the lens of connoisseurship, so they’re more interested in the physical attributes of specific works and their overall condition as opposed to their significance to social or cultural history (although this is still important). Nevertheless, they’re intensely rich resources filled with useful facts, insights, and images, and they’ve proved invaluable to my understanding of these historical objects.

The most helpful information has pertained to the firm Jumeau, which supplied a lot of automaton makers with bisque doll heads. Founded in the 1840s, Jumeau transformed the doll market in the 1870s by introducing articulated dolls with the proportions of children. Prior to this, French dolls were essentially presented as adults modeling the latest fashions. With these new dolls, however, children played with miniature versions of themselves, further underscoring the overall sentiment nineteenth-century consumers experienced toward childhood. Additionally, Jumeau ensured a constant audience of consumers by changing the dolls’ fashions every season and making them the subject of elaborate advertising campaigns through children’s books and other media, techniques not terribly unlike the American Girl dolls we see today.

What was most interesting to me though, was the story behind the head for one of the automatons in the Barry collection, Léopold Lambert’s Crying Child with Polichinelle. Of all the automatons, I find this one one of the most unnerving due to its frank yet aestheticized display of raw emotion. With her mouth frozen in a wail and a large tear permanently affixed to her cheek, the girl remains arrested in despair, forever beyond our consolation. And unlike a painting or a photograph of a crying child, which suggests a single moment affixed in time, this sense of permanent misery is only confounded through the automaton’s motility. Her movements give her a sense of vitality and presence, she’s not simply in the room but is experiencing space here with us, but her sobbing face remains immune to any comforting or consolation.

Ruminations on emotion aside, I knew that Jumeau had supplied the Crying Child’s head to Lambert. What I didn’t know was that Lambert had specifically commissioned the crying head design, along with several other character heads, as part of a new series of automatons exploring the emotions of children. Many automaton makers, including Lambert, used stock doll heads with the necks modified to accommodate the turning, bobbing, and other movements associated with automatons, but in this instance, he wanted new heads designed specifically for his firm. Some would cry, others would laugh, some would even whistle. Not all of these designs ended up being used, but the Crying Child head was one of them. Indeed, there are automaton catalogs from the 19th century showing the Crying Child as one of Lambert’s offerings. The fact that Lambert specifically wanted to design an automaton of an unhappy child, and commissioned one of the most renowned doll manufacturers of the 19th century to create the head for that design, is something I find extremely interesting. This is partially because I can’t quite understand why anyone would either want to design one or have it in their parlor. I get the interest in designing or purchasing circus performers and musicians, but a crying child? Yet there was clearly a market for it, as there are several out there that survive.

Unhappy children aside, this has also been a time of reflection. With the halfway point of the year having come and gone, we’ve started to take a look at out prospective checklists and begin narrowing down objects. After all, as fun as it is to think about the potential of an exhibition and the innumerable directions it can take, at some point you have to start narrowing down your themes and figure out which objects you actually want to use. At this point, we have a fairly good sense of the show’s thematic content, but we need to finalize the checklists so we can get the paperwork in order. We’re in a good place and still have time and room for flexibility, but we’re definitely shifting away from the more conceptual stages of exhibition research and focusing more on the logistics and expenses of shipping and gallery prep. It’s exciting because it means you’re moving closer to having the exhibition become a manifest physical experience, but there’s also a touch of melancholy because the time of infinite possibilities has come to an end. When I was working in Roswell I rarely had time to reflect on this transition because the exhibition schedule was always so full. With the Barry Art Museum though, I’ve got the time and space to reflect on exhibitions as process as well as product, and I really appreciate that.

I’m back and refreshed from Florida though, so stay tuned for more updates next month.