I’ve been thinking recently about one of the first jobs I had after I finished my Master’s degree. From the fall of 2010 to the spring of 2011, I was a curatorial intern at the Dallas Museum of Art. During those nine months, I gave tours, curated my first exhibition, helped write a couple of grants, all while getting to know the city of Dallas. It was a fun time, and I got to see a part of the country that I never expected to visit.

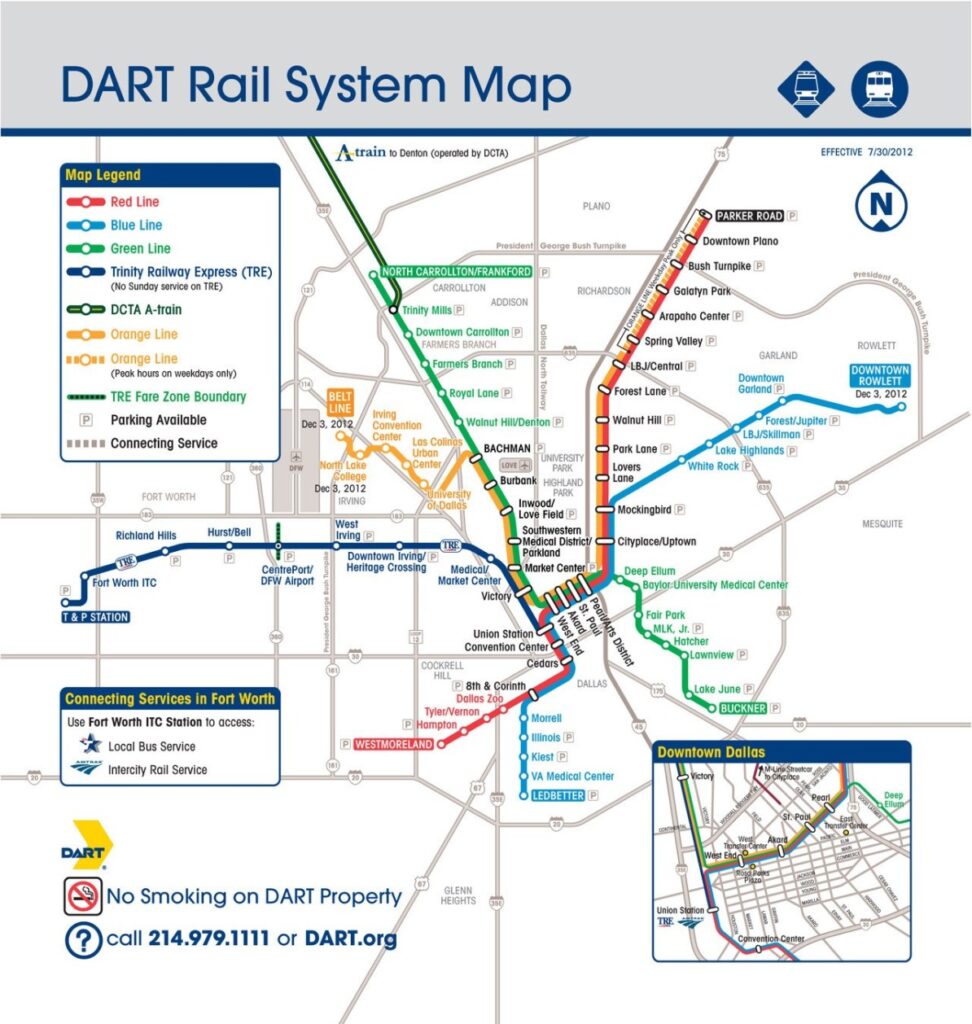

Yet what I’ve been thinking about hasn’t been the actual job I had at the museum, but the commute I used to take to get there. Since the stipend was relatively modest, I couldn’t afford the swanky apartments downtown, so I rented a room from a woman living in one of the neighboring suburbs. Because I didn’t have a car at the time, I relied on public transit to get to work. Every morning, I would ride a bus for about 45 minutes, and then walk an additional 15 minutes to get to the museum.

During the course of that bus ride, I watched the demographics of the city change. When I would get on, I was usually the only white person on board. Everyone else was Black or Latinx, and the suburb I lived in, originally built in the 60s, had similarly shifted from a predominantly white population to people of color. By the time I arrived at the museum and the neighboring arts district downtown, nearly everyone was white. The closer I got to the so-called nicest parts of the city, the whiter its residents became.

When I look back on my time there, what also stands out to me is how much walking I had to do to reach public transit centers. Although there was a bus stop very close to my house, getting to the museum was another matter. Aside from a quaint trolley going to Uptown, there was no light rail station or bus stop going directly to the museum. In order to get to work, I needed to walk at least half a mile. It was as though the city didn’t want any kind of bus station near the museum. I didn’t think about it much at the time, but in retrospect, it makes me wonder what kind of audiences can really access the museum in its related spaces.

The exposure I got to the demographics of cities while living in Dallas, limited and brief as it was, has helped me appreciate the final group of readings in my history list, which have focused on urban segregation.

Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law explores residential segregation through the lens of government action. The author argues that, as the title implies, residential segregation was promoted and enacted by the government on all levels, through legislation, Supreme Court rulings, and federal programs such as the CCC and the Affordable Housing Act. The book centers the significance of racism to government policy on all levels, local, state, and federal. It advocates for a much more aggressive stance toward desegregation, arguing that residential segregation is not only symptomatic of institutionalized racism, but is unconstitutional. Jessica Troustine’s Segregation by Design looks at segregation as practiced on the municipal level. Taking a more local perspective, she argues that city governments have played a seminal role in the segregated nature of American urban environments by giving precedent to white property owners concerned with maintaining their property values while also benefiting from public goods. She posits that white property owners should acknowledge their privilege by supporting the construction of multiunit complexes and other forms of public housing in their neighborhoods. She also suggests that the federal government should take a stronger role in promoting desegregation practices, positing that when flight is not an option, whites are more likely to willingly integrate with other populations.

While The Color of Law and Segregation by Design focus on urban segregation as a broad national problem, other texts have focused on specific cities. Colin Gordon’s Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of an American City looks at urban decay through a case study of St Louis. In addition to the monograph, Gordon has also done a digital mapping project enabling viewers to visually follow along with St. Louis’s changing demographics. Gordon focuses on the intersections between the anxiety of white homeowners and the codification of real estate practices intended to protect those rights. He is particularly critical of the idea of home rule, or enabling cities and suburbs to legislate themselves, as he believes this encourages communities to view one another as competitors for resources rather than collaborators. As a result, the communities with the most financial resources at hand, white suburbs, are more likely to get what they want, while black populations are increasingly constrained to decaying, urban areas. While Gordon concentrates on real estate practices, Tyina Steptoe’s Houston Bound looks at the culture of urban segregation. She looks beyond the black-white binary to focus on race relations and culture within Jim Crow communities, with a focus on the 1920s through the 1960s. Concentrating on Houston’s East Texas, Creoles of color, and ethnic Hispanic populations, she argues that the concept of race in the segregated parts of Houston are culturally complex, impermanent, and changing throughout the 20th century. She looks specifically to cultural forms, such as sounds and music, as well as the physical experience of urban spaces. Through these explorations, she complicates Houston’s racial identities by looking beyond legislative definitions to consider cultural exchanges.

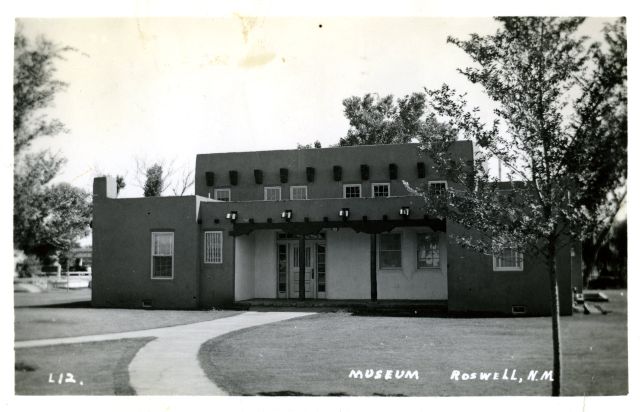

With regard to my research on the Community Art Center project, these readings have been relevant when thinking about the kinds of buildings used for these spaces and where they were situated. A particularly striking contrast is the one between the Roswell Museum and the South Side Community Art Center. The Southside Community Art Center is based in the southern part of Chicago, which is a historically Black community. It is housed in an old Brownstone mansion, which was built in the 19th century. When it was built, it was part of a white neighborhood, but during the 20th century, as whites moved out of the city center, the community became predominantly Black. The South Side Community Art Center then, architecturally attests to the history of the changing demographics of the neighborhood. By contrast, the Roswell Museum and Art Center was a brand new building when it opened in 1937. Additionally, it was built in the northern part of town, about a block or two from the New Mexico Military Institute and adjacent to what is now designated as the historic district. Roswell, for those who are familiar with it, know that the white population primarily lives in the northern part of the city, while the southern part of town is mostly Hispanic. The Roswell Museum then, is actually housed in the white part of town, and not surprisingly perhaps, attracting Hispanic visitors has been an ongoing challenge.

Thinking about urban segregation and housing has also extended into my personal life as well. Brandon and I happily rent a townhouse in New Town, but like a lot of people, we have talked about buying a place of our own someday (emphasis on someday, given the state of things). As part of those conversations, one issue we have talked about is whether we would rather buy a single-family home or a condo. While we both acknowledge that single-family, detached homes hold a lot of appeal, not least because they have been touted as the ideal in terms of the homeownership dream, they also bother us for a lot of reasons. While you get the benefit of privacy and the space to indulge all your hobbies, from an ecological standpoint single-family homes are inefficient and demand more space than you need. Looking at housing from the perspective of the readings I’ve been doing, moreover, single-family homes have historically been the privilege of white people. Not only have suburbs preferred white residents over people of color, but suburban neighborhoods have also used their financial and legislative powers to limit affordable, multiunit housing. As a result, the housing that is available remains expensive and unavailable to the majority of working-class people because there is a finite amount available. The single-family home that has been touted to us as the dream in terms of ownership relies on the exploitation of other people, while the finite supply of housing due to an overwhelming cultural preference for the single-family home further contributes to high housing prices overall. When we talk about housing, Brandon and I can’t help but think that aspiring to the single-family home perpetuates this exploitation. At the very least, we agree that we should actively support the construction of multiunit and public housing in our neighborhood, wherever we eventually settle.

Not that I haven’t thought about these kinds of issues before. When I was in Roswell, I can remember attending a City Council meeting where the councilors debated getting rid of one of the polling centers to save money. Not surprisingly, perhaps, this polling center was located in the Hispanic part of town, and the counselors who supported its removal were white. With American studies though, you realize that if you’re going to deal with the United States and its culture, whether in a historical or contemporary context, you have to deal with race. Everything about our history and our infrastructure, whether it’s the housing markets or art markets, inevitably comes back to race in one form or another. The main thing that I’ve learned from these history readings isn’t so much the idea of systemic inequality, but rather the subtlety of its pervasiveness, and the hard work it will take to dismantle it. Based on what I’ve seen, that will be very hard work to do indeed, but vital to our future.