If you’ve been reading recent posts and getting the impression that I’ve been traveling more than usual lately, you’re absolutely right. Last month, Brandon and I flew over to Scotland so that I could complete my assistantship as the JDP Fellow. Less than two weeks after that, we traveled to Bentonville so that I could visit the Crystal Bridges Museum while he attended a conference. And less than a week after that, I hopped up to New Jersey to give a talk at the Morris Museum, which I’ll be sharing today.

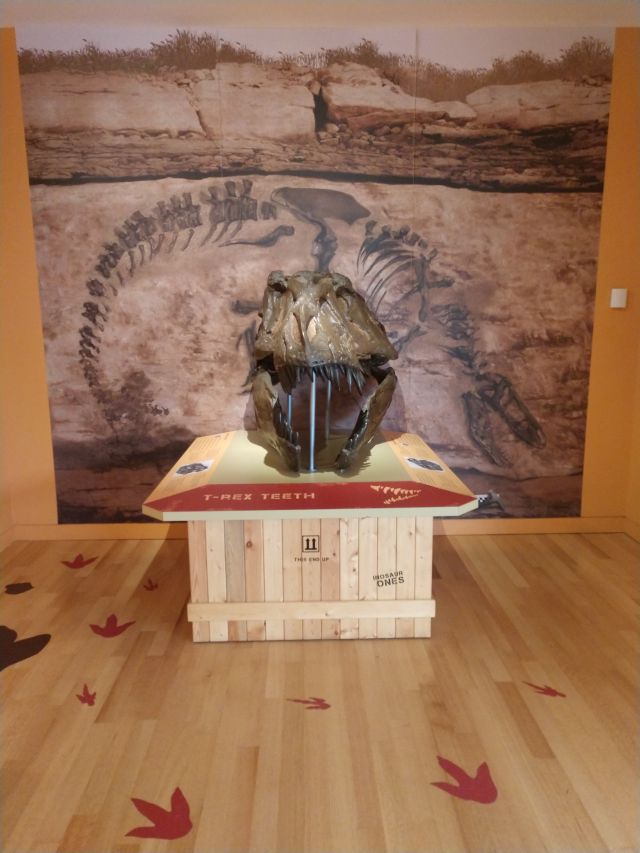

Located in Morristown, New Jersey, the Morris Museum is an eclectic institution. Over the past century or so of its existence, it’s collected minerals, fossils, artwork, Indigenous artifacts, and other objects. Its actual building reflects its eclecticism, with part of the collection occupying an early 20th-century mansion, and the rest living in a more contemporary structure.

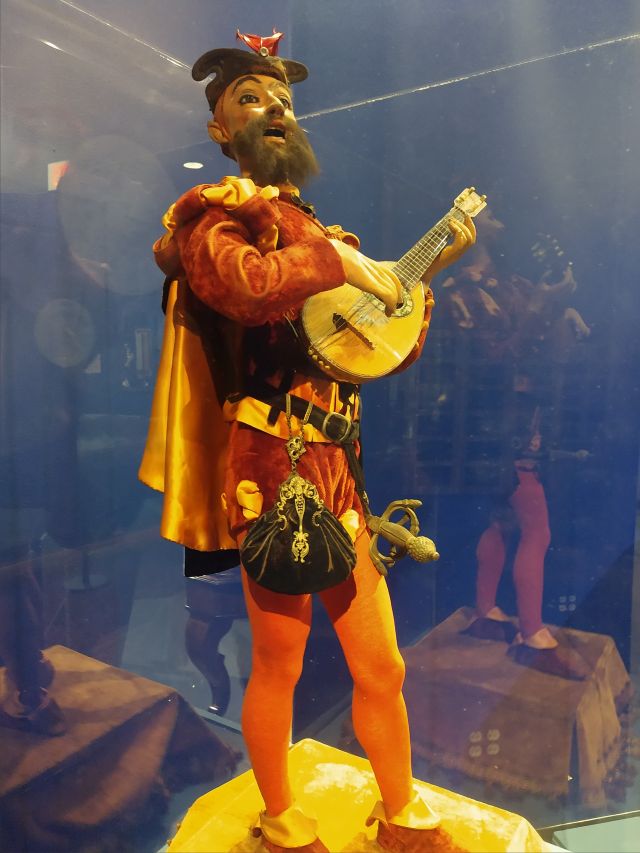

Yet the museum is probably best known for one particular collection within its holdings: The Murtogh D. Guinness Collection of Mechanical Musical Instruments and Automata. Consisting of over 700 objects, this collection was amassed by Murtogh D. Guinness, a member of the renowned brewing company family. The collection was donated to the museum in 2003 under the conditions that most of the collection be available for the public to view at all times. As a result of this stipulation, one of the distinguishing features of the museum is its visible storage, allowing viewers to see the objects even when they aren’t in the galleries.

The automata, or rather the people who admire them, are the reason why I went up to give a talk. In 2018, the museum began hosting an event called Automatacon, a worldwide celebration of automata where collectors, makers, and scholars come together and share their enthusiasm through lectures, exhibitions, demonstrations, and just having a space to talk shop. After a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic, the museum resumed hosting the event, with the convention taking place May 21 and 22. An exhibition of contemporary automata was on view in tandem with the convention (and beyond), and many of the exhibited artists participated through illustrated lectures and panels.

I talked about Motion/Emotion: Exploring Affect from Automata to Robots. Since the Barry Art Museum has its own automaton holdings, we thought this would be a good audience for sharing the museum collection. We also hope that some of the attendees will either visit the museum during the Motion/Emotion run, or check out some of the online programming and virtual tours. In essence, my job was to put the museum out there for an audience that would enjoy a specific part of its collection.

The highlight for me personally was definitely visiting the museum’s automatons. Early on in the conceptual phase for Motion/Emotion, we looked into the possibility of borrowing pieces from the Guinness collection. Ultimately we decided to move in a more contemporary direction, but I still got to know several of the pieces through condition reports, thumbnail images, and conversations with conservators. After admiring these works from a distance, then, viewing them in person was almost like seeing old friends. Better yet, Jere Ryder, the museum’s lead conservator, activated a handful of automata and musical instruments for conference attendees, allowing us to experience them as the multisensory, kinetic objects they’re meant to be.

Given the often whimsical nature attributed to automata and mechanical musical instruments, the museum has leaned into the immersive, playful side of exhibit design while emphasizing the objects’ history in relation to technology and mechanics. I particularly liked how the automata are displayed in a recreation of the Parisian distinct where many of the most prominent automaton designers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lived and worked. Seeing these objects in a facsimile of their original commercial space helps to remind viewers that these objects were both commodities and a part of the Parisian visual culture at large, beckoning visitors from shop windows with their mechanized antics and striking costumes.

As with any convention or conference, Automatacon was also a good opportunity to meet new people and reconnect with familiar faces. Elizabeth King, one of the artists featured in Motion/Emotion, was giving a talk on several sixteenth-century automata she’s been researching for a book, and it was a good chance to catch up on our lives since the exhibition’s opening. I’d met Jere Ryder virtually through Zoom meetings, but this was our first opportunity to interact in-person. I met both of the museum’s curators, and had a good time comparing notes on our scholarly research and museum work. And of course, there were the automata enthusiasts themselves, who hopefully will make a trip to Norfolk in the near future.

Yet if it event itself was fun, the unexpectedly complicated, tortuous return to Williamsburg was an important reminder of the need to prioritize my time when it comes to external commitments. What happened was that I was going through airport security, my flight was cancelled with no possibility for rescheduling that day. After looking into other options, from rebooking the flight to taking a train back home, to even Brandon offering to drive up and get me, I rented a car and drove myself back to Virginia. Instead of getting home in the early afternoon, as would have been the case with my original flight, I got home around 7:30 in the evening. A more spontaneous, pre-pandemic version of me might have rescheduled for the next day and used the delay to go visit the Newark Museum, but at this point, after so many back-to-back trips (and two more scheduled within the next three weeks), I just wanted to go home. I also didn’t fully trust the airline to not cancel my flight a second time, as their explanation was perfunctory at best.

The change in travel plans was an important reminder of the need to prioritize my time. One of the things I’ve missed since being in grad school is public speaking, and working with the Barry means I have opportunities to talk with audiences beyond a scholarly conference setting in the form of gallery talks and lectures. Yet as much as I enjoy these events, my dissertation remains my top priority. As fun as speaking at Automatacon was, it ultimately demanded too much of my own time. I essentially lost a weekend, a time I use to rest and recharge for the next week of research and writing, and I don’t want that to happen again. In the future then, I’m going to be more careful about how I use my time, and be more selective about events I do outside of my dissertation work. In the case of the Barry, this means sticking to local or virtual speaking engagements.

But all that said, it was still really cool to see so many automata in one place. In spite of the travel difficulties, I’m glad I visited the Morris Museum.