Over the years, I’ve been working my way through a list of museums I’d like to visit. Some of these institutions, like the Louvre or the Met, are world-famous. Others, like the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma City, or the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia (this latter one hasn’t happened yet but it will someday) are more specific to my quirkier interests.

Another institution I’ve been wanting to visit is the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas. As a curator who’s focused primarily on American art, I knew it was an excellent collection, and had seen pictures of its beautiful site and surroundings. But I’d also heard it was doing innovative things in terms of its collecting practices and interpretation, and have been wanting to see those efforts for myself. Since the museum isn’t located near friends or family though, the years went by and it remained unvisited.

So when Brandon mentioned a few months ago that he had a work conference taking place there in May, I knew this was my chance. Brandon is a member of PACCIN (Preparation, Art Handling, Collections Care Information Network), and every other year they have a conference. Two years ago it took place in Amsterdam; the destination for the next session has yet to be determined. This time around, it was happening at a museum I’ve been meaning to see for over a decade, so I accompanied Brandon on his work trip, as he had done with me when we traveled to Scotland a few weeks ago.

The conference took place over two days, with participants arriving at the museum at 8 am and sessions ending for the day at 5 pm. I rode over on the shuttle buses, splitting from the group as they headed to their first sessions. Since the museum didn’t open to the public until 11, that left me with plenty of time to explore the site’s extensive art trails. As someone who loves art and being outside, these trails were definitely a highlight of the visit, synthesizing two great loves of mine into one wonderful experience. Seriously, walking through the forest and taking in art while listening to songbirds and catching glimpses of furtive deer or turtles is nothing short of wondrous.

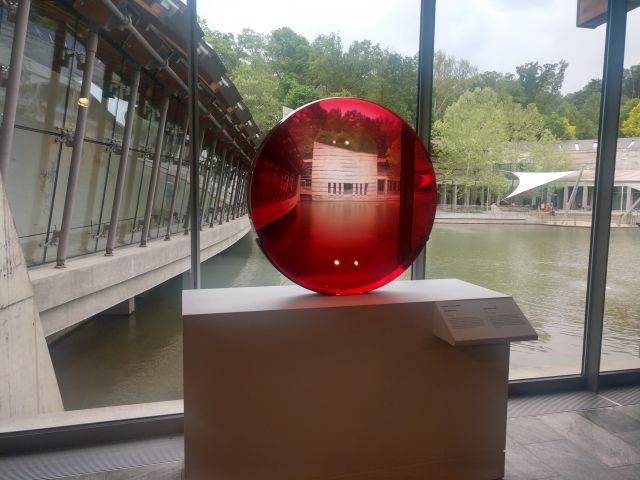

The museum itself also more than lived up to my expectations, and having two full days to visit meant I didn’t feel rushed going through it. The architecture, both inside and outside, is impressive, feeling both contemporary yet organic through its use of materials and ample windows. The collection is excellent. It’s got its share of recognizable hits like Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter, well-known pieces that help draw in crowds. Yet it’s also one of the most diverse I’ve seen in terms of representation, with many examples from Black artists, Indigenous artists, Asian American artists, Latino artists, and others on view.

The museum even has an architectural site in its holdings via the Bachman-Wilson House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Originally located in New Jersey and rebuilt at the Crystal Bridges in response to ongoing flooding at the original site, the house is a striking example of Wright’s so-called Usonian architecture, structures intended for middle-class audiences that offered Wright’s horizontal, nature-infused aesthetic at a more affordable price than his earlier commissions.

Nor was my visit limited to the museum’s holdings. In addition to the collection itself, I visited The Dirty South, an exhibition I’d seen at the VMFA last year. Seeing the show again here was an opportunity to not only see some outstanding works a second time, but to see how two different museums presented the same materials. I also had the chance to see an installation by Julie Alpert, a Roswell Artist-in-Residence alum whose career has continued to flourish. Additionally, it turned out that one of my old friends from Shelburne Museum, who’s now the Preparator at UVM’s Fleming Museum, was also attending the conference, which was an unexpected but wonderful surprise. All of these different facets made for an outstanding visit.

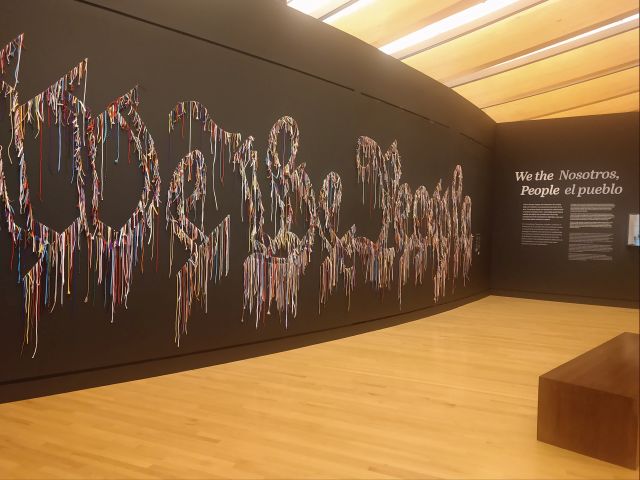

But what I especially appreciated about Crystal Bridges was its approach to interpretation. All of the labels are bilingual, with English and Spanish text printed in the same size and at the same level. The didactics themselves address racism, settler colonialism, and disinformation, topics that are difficult but absolutely need to be discussed. The labels remind viewers that the art they see are not objective views of the past, and to be wary of nostalgia. I also appreciated how the museum introduced visitors to contemporary art, which often intimidates people who aren’t familiar with it. Throughout illustrated timelines, the museum showed how contemporary art, far from being unrelated to historical art, deeply engages it. Many labels encouraged viewers to focus on formal qualities such as line and color as a means of entering the work before delving into more thematic content. Some labels featured text written by elementary school students, validating their interpretations while also shifting the authority away from the museum and onto the viewer.

The museum’s smart approach to interpretation also extends to the actual placement of art. Indigenous art is included throughout the galleries alongside other objects, challenging the misconception that Indigenous people only exist in a distant, mythical past. A Dentzel carousel animal is paired with paintings by Whistler and Homer because they all address leisure. A Horace Pippin landscape is placed beside Durand’s Kindred Spirits because they both address spiritual topics through the medium of the idealized, invented landscape. A clip from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times plays alongside paintings and prints of industrial life made during the same period. Instead of grouping objects by geography or medium, the museum takes a thematic approach, enabling works in different media and by different artists to coexist in the same space.

The museum also works with contemporary artists to provide additional interpretation to the permanent collection. An especially striking example of this was Beth Lipman’s Belongings, a glass installation created in 2020. The installation is all about representation and omissions from narratives of history. Lipman created the work in response to an 18th-century portrait of Abigail Levy Franks, itself part of a group of portraits depicting members of a German-Jewish family based in New York. Having this family group on view is already significant because it underscores the Jewish presence in the American colonies, but Lipman goes further. Using opaque glass, she made a travel trunk filled with objects. Since the glass is opaque, however, viewers can’t fully see what’s inside of it, an obscuring that comments on the unknowability of the past and the selective history of the portraits themselves. Among the objects included in the trunk, for instance, are chains. As successful merchants working in 18th-century colonial America, the Levy Franks engaged the slave trade, yet their portraits do not betray this connection. Like today’s Instagram posts, these portraits do not present an objective view of the past, but instead the sitter’s interpretation of what they wanted the viewer to see. Through the striking visual example of the glass trunk, Lipman encourages viewers to think about not only what has been lost to history, but how historical figures have shaped subsequent interpretations through their own selections and omissions. By working with artists like Lipman, the museum uses contemporary art as a means of deepening the interpretation of its historical collection, underscoring not only the ongoing dialogue between historical and contemporary art, but the ability of art to engage different ideas, topics, or questions.

In short, what the Crystal Bridges Museum offers to its viewers isn’t a flag-waving, patriotic display, but a thoughtful consideration of the messiness of American art, celebrating diversity while recognizing ongoing inequities. That doesn’t mean it’s perfect. One can’t forget that it’s inexorably linked to Wal-Mart, which has long been critiqued for its business practices. More broadly, the act of decentering whiteness and decolonization, as Brandie Macdonald argues, is an ongoing, unfinished act. The Crystal Bridges installation, as well-done as it is, does not represent the last word in making museums more equitable. But it is an important contribution to this much-needed work, and it is by far one of the most progressive installations I’ve seen when it comes to interpreting American art. I came away from the museum feeling energized and excited about what I had seen.

It also offered a tantalizing glimpse into a world where art is part of daily life. Admission is free to the permanent collections, and the walking trails are open from sunrise to sunset. On the ride over from the airport, our Uber driver mentioned that his teenage daughter regularly visited the museum after school to relax and decompress. During the two days I spent there, I saw bikers and joggers getting their daily exercise along the trails. I shared space with rambunctious middle schoolers as we sat inside James Turrell’s The Way of Color. I watched conference attendees have lunch underneath Louise Bourgeois’s Maman. I saw the museum as not just a gallery, but a community space, something that Progressive activists, FAP administrators, and others have mused about for at least a century.

In short, this was definitely a trip worth taking.