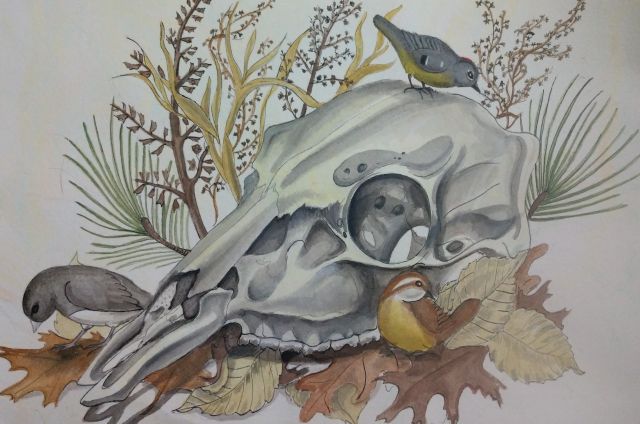

Last month I talked about the still life series I’ve been planning around a deer skull in different seasons. Today, I’ll show you the first entry in this group, Williamsburg Still Life: Winter, which I finished a couple of weeks ago.

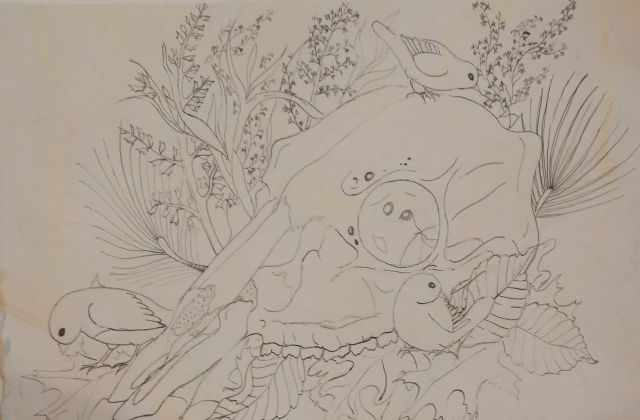

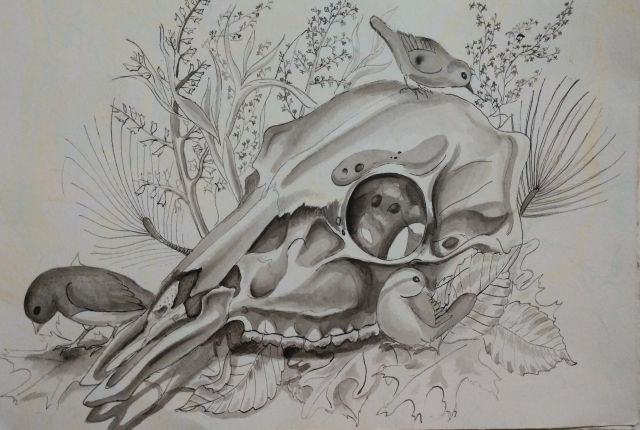

I completed this drawing over two weeks. I worked on it during the evenings, after I had finished my scholarly and curatorial responsibilities for the day. I started with a pencil sketch based on previous studies, which I then outlined in pen and ink. I added values with ink wash, followed by acrylic diluted with water to resemble watercolor. I then repeated the process in reverse, starting with color, then inkwash, and finally adding details with pen and ink.

While I’ve already discussed how this series quotes art history through its evocation of the vanitas, I’ve also started thinking about other ways it engages histories of art. More specifically, I’ve been reflecting on how the practical choices I’ve made with respect to medium, scale, and even the times I choose to draw engage longer histories of women artists negotiating the tensions between their creative work and domestic and professional labor.

When I first started planning this series, I imagined doing larger drawings, at least 18″ x 24″, maybe 24″ x 36″, to give the works a monumental quality. The final drawing ended up being much smaller, however, around 8″ x 11″, as I decided that working with smaller sheets I already had available would be both more cost-effective and more conducive to working in a living room, as I don’t have an easel or related art-making furniture. While I ended up liking the intimate scale, it did get me thinking about my personal history of creating small works. The daily abstractions I did in 2019, for instance, were each 2″ x 3″, and the largest single painting I’ve done since college has been 16″ x 20″. I’ve painted designs on preserved eggshells and made prints small enough to glue on Christmas cards, but I rarely attempt larger works.

This hasn’t always been the case. When I was in high school, my parents let me cover one of the bathrooms in our house with an ocean-themed mural. As a graduate student at Williams, I painted a mantle-sized recreation of the Villa of the Mysteries on butcher paper for a Halloween party. When I was in Vermont, I occasionally pulled impressions up to 11″ x 22″. Yet for the last several years I’ve been working on a small scale. When did this change occur?

This isn’t the first time I’ve thought about this. I know my work has gotten smaller due to a combination of finite money for supplies, lack of studio space or the money to rent such a space, and time due to working and/or studying full-time. As such, it’s easier to create smaller works that accommodate my time and demand minimal clean-up. Indeed, the largest piece I’ve made recently isn’t a painting at all, but a knitted blanket, perfect for a fully-carpeted rented apartment with white walls.

I had always thought about these creative choices in practical terms, that I made the selections I did because my living conditions or work obligations necessitated them, but after reading Painting by Numbers by Diana Seave Greenwald, I’ve been recontextualizing my personal art practice within a longer history of time and space constraints on creativity. Greenwald reexamines the canon of nineteenth-century European and American painting using a hybridized approach combining formal analysis and other conventional art-historical techniques with digital humanities practices such as quantitative analysis and distance viewing. Through this approach, she revisits long-held ideas about art history, like the popularization of landscape painting during the nineteenth century. Given my interest in digital humanities, I initially read this book for its quantitative approaches, but I’ve also found it resonating with my creative practice.

Greenwald’s chapter on women artists especially struck me with respect to my own artistic pursuits. Wondering why so few women artists ended up in permanent collections despite exhibiting at salons and other events consistently, Greenwald looks at the actual checklists of pieces featured in these shows to see what women were painting. She argues that women most often painted smaller works such as still lives in watercolor, works that accommodated limited time and space due to domestic duties or difficulty in accessing studio space. Yet these works were less likely to be acquired by museums due to a hierarchy of fine arts favoring larger oil paintings, a bias that becomes evident when you scan the contents of museum collections. Unless women artists were willing or financially able to forego marriage and concentrate exclusively on their careers, as Rosa Bonheur or Mary Cassatt did, domestic obligations and spaces dictated the kind of work they could do and its likelihood of being seen. Even when museums have acquired watercolors from women artists, moreover, their light sensitivity means they cannot be displayed for lengthy periods of time like oil paintings can, further limiting their visibility.

Again, this isn’t the first time I’ve thought about these issues, but what really struck me are the parallels between my creative practice and those of nineteenth-century women painters concerning time and space. I have no children and don’t plan on having any, but I still work full-time and contribute to domestic labor through cleaning (Brandon does the cooking). And like so many nineteenth-century women, I focus on still life instead of portraiture or other subjects that require large chunks of time and focus because I can work on them in smaller increments in the evenings. And for easy clean-up, I use watercolor and water-soluble ink instead of oil paint. While conditions have changed for women a lot since the nineteenth century, as Greenwald elucidates in her book, in a lot of ways they haven’t.

Yet Williamsburg Still Life: Winter isn’t just about my general working conditions as a woman making art while holding a different full-time job. After all, I have accessed studio spaces in the past through museums and public art centers, and will likely again in the future. But that’s the key distinction right there: I have used these spaces in the past, and probably will in the future, but not in the present.

This piece, and ultimately this series, is about living and working in 2020, through its scale and medium and well as subject matter. To put it another way, it’s a work made within the home, using objects and animals I collected or sketched near that home. Every facet of its material nature, from its intimate scale to the use of local subject matter, asserts its creation as a work made at a time when using public studio spaces hasn’t been the best option. As such, the conditions of the home have informed this work’s scale, medium, and subject. While making art at home isn’t new for me, given the ongoing realities of working during the pandemic, it feels especially poignant at the current moment.