A few weeks ago I was reading about the history of shipping containers and their influence on society. The book, appropriately enough, was titled The Container Principle, by Alexander Klose. His central argument is that the concept of containerization, of putting things into a standard-sized box designed explicitly for moving stuff to other places, has shaped globalization through enabling mobility, encouraging the standardization of forms, and the hyperconsumption underpinning late capitalism. He then explores the container’s significance through a series of chapters exploring its development, with the modern shipping container associated specifically with oceanic transport emerging during the 1960s.

A key part of containerization, Klose argues, is the emphasis on movement and transport as opposed to strictly storage. He posits that older forms of storage-based furniture, such as blanket chests, were tied to specific objects, and by extension a sense of rootedness to place and domesticity. To continue with the blanket chest example, storing blankets brings up associations with the bed, which is kept in the home, which is the site of procreation, and so on. Shipping containers, on the other hand, are designed for moving stuff to different places. Their design revolves around efficient, all-purpose storage, rather than be tailored to the specific objects they hold. It doesn’t matter what goes into them, whether it’s blankets or electronics. What counts is that they efficiently get these things from place to place. Their primary association isn’t with domesticity or sense of place, but rather their capability for transport.

I’ve been thinking about Klose’s concept of containerization within the framework of my previous experience as a curator. During my five years in Roswell, I spent a lot of time dealing with the movement of artwork. Sometimes I moved art myself, usually in the back of my car. Other times artists shipped their works themselves in a variety of packaging. Still other times we hired professional art shippers to move objects for us. What stands out from all of these experiences, however, is not simply the enhanced mobility of the art object as rendered through modern transportation forms, but an emphasis on their uniqueness, their materiality, as things.

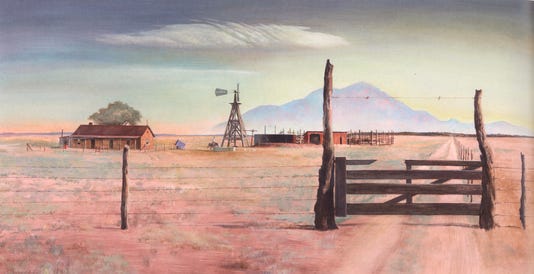

The most vivid example of this occurred while working on the exhibition Magical and Real. For the show’s initial opening at the Michener Art Museum, we had about 20 of our works shipped to Doylestown, Pennsylvania, through a company called US Art. The day the art shippers arrived, we blocked off a gallery where they could wrap each of the works and place them in crates built specifically for the show. What struck me (and assuaged my anxieties about having the collection travel across the country) was the specificity surrounding the crates. Each box had been lined with thick foam passing cut to the exact framed dimensions of each work. In other words, each foam slot could only accommodate one specific work. No other painting would fit correctly. The process of transport may have been modern, but as a container, the art crate underscores rather than erases the object’s individuality.

We encountered that uniqueness again when the objects came back for the Roswell installation. This time, we not only had our own works, but all the other paintings from the Doylestown installation. Yet each crate and package, no matter which company manufactured them, underscored the individuality of the object through their construction. Those crates may have been designed expressly for movement, but they could only move one specific object.

That sense of the art object’s uniqueness is a quality underpinning art travel as a genre. Walter Benjamin speculated in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” that photographic images of artwork would dispel their seeming aura of uniqueness, but the number of people willing to undertake substantial journeys to see works of art in person suggests that the power of the original has not entirely dissipated. Whether we’re visiting the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, or seeking unique immersive experiences such as Meow Wolf, art-related tourism is a big industry, to the point that scholar Adrian Franklin has recommended that we recognize it as a field distinct from tourist studies. Even at the Roswell Museum, we had visitors who came expressly to see singular works like our sole Georgia O’Keeffe, Ram’s Skull with Brown Leaves, or Peter Hurd’s The Gate and Beyond.

Then there’s the travel that works of art undertake to reach new audiences, suggesting that the experience of viewing the original object in all its materiality is a more profound encounter than viewing a reproduction. To take a recent example, the Obama portraits at the Smithsonian American Art Museum are ubiquitous on the Internet, yet they’re still about to go on a national tour to various museums so that audiences unable or unwilling to travel to DC can see them in person. Even in an age defined by digital images, we continue to valorize the material power of the original work of art as a sensory experience.

I speculated on the aura of art objects in my mobility class last semester. For my final project, I argued that the uniqueness attributed to art objects stemmed in part from a sense of rootedness as articulated by anthropologist Liisa Malkki, or a connection to a specific place, culture, or conceptual idea. This rootedness, I argued, offers viewers a sense of stability and connection. By looking at the original art object, they get to experience that rootedness directly, without the intermediary of a photograph or digital image. Its physical presence, in other words, suggests a more tactile, authentic link to a sense of tradition or place, verifying our own experience of the world through the medium of our bodies.

But why does any of this matter? What difference does it make whether we understand the motivations behind why art objects travel, or why we undertake journeys to see them? Who cares how a crate is molded to a painting’s dimensions beyond knowing that it minimizes vibrations?

On an ecological level, it is important. As art museums and similar institutions grapple with climate change through their exhibitions and sustainability practices, they’ll have to confront the various ways they contribute to carbon emissions. Exhibitions, especially traveling ones, produce a significant amount of waste stemming from their ephemerality as experiences. Just as a shipping crate for a painting is fitted to one work’s exact dimensions, exhibition texts are catered to one specific show. Once that show comes down, those labels, vinyl letters, and panels get discarded. Crates generally can’t be used for other paintings unless their modified, a process that requires adding or throwing away foam and other materials. Then there’s the problem of transporting artwork and emissions resulting from transport in trucks or places. And the list goes on.

Russell W. Belk grapples with the role of museums in promoting consumption in his book Collecting in a Consumer Society. By celebrating the materiality of individual objects and placing primacy in things as the most effective means of preserving a culture, he argues that museums have promoted collecting and consumerism. In displaying material objects, particularly those of the rich, as things to be celebrated, museums demonstrate by example that it is inherently good to possess things. But what happens when the collectors who cherished these things die, or are no longer able to maintain their objects? What happens when children or other relatives are not interested in their parent’s collections? What about all the stuff that gets thrown away during purge cleanings? Where does it go? As these questions suggest, the unfortunate part of identifying yourself through your objects, of projecting your uniqueness into your things, is that no one else may care for them in the same way, because they do not see themselves in them. One person’s treasure is another’s trash.

So what does all of this have to do with containerization? As an art historian interested in how travel infrastructures influence art accessibility, I’m intrigued by how modern transport forms and materials have shaped how and where we move art. While some concepts such as transport via highway are distinctly modern, other concepts like the uniqueness dimensions of crates seem strangely resistant to standardization, even as the crates themselves follow certain procedures in terms of dimensions and building quality. In short, modern art transport, as far as I can tell, continues to affirm the uniqueness of the art object even as the art image becomes increasingly ubiquitous through digital means. Whether or not that’s the best model for our planet, however, is a question we’ll have to confront. Indeed, it may be time we reevaluated what it is we value about art in the first place.