As with last month’s post, my ongoing exhibition work with the Barry has been moving in two interrelated but distinct directions. On the one hand, I’ve been continuing my research into robots and automata, focusing particularly on their cultural histories. At the same time, we’ve been addressing the more practical side of exhibition work by actively reaching out to artists and museums while continuing to refine our primary organizing themes.

Regarding research, one of the more interesting books I’ve recently finished is Dustin A. Abnet’s The American Robot, which looks at the cultural history of robots in the United States from the late 18th century through the present. A key part of his argument is that the history of the robot as an American icon is inextricably linked to privilege. This doesn’t mean that white men were the only ones to interact with robots or to think about them through fiction and other media. Women published short stories about robots in 19th-century literary magazines, for instance, often while critiquing male attitudes toward women and domestic labor. Magazines like Ebony and Jet, in turn, published stories about Black youth building robots, reminding their readers that technology has never been the exclusive domain of white, cisgender men. But it was white, male perspectives that were most likely to get published in magazines, shown in movies, or rendered in public policy. As such, the resulting conception of the robot is one that enables white men to enjoy their privilege without guilt. Rather than address infrastructures of inequity by sharing domestic labor or acknowledging complicity in suffering, robots in popular culture perform labor without complaint, offering a guilt-free version of enslavement, misogyny, and other forms of exploitation.

In another volume, Techno-Orientalism, I continued reading about the potentially dehumanizing effects of technology when it becomes conflated with specific groups of people. While not exclusively about robots, its discussion of the ways Western sci-fi writers, artists, and creators have both fetishized and othered Asian people by appropriating Asian aesthetics to create exotic techno-futurist landscapes, effacing emotional complexity by equating Asian people to machines, and other tropes felt especially relevant. As the victims from Atlanta’s shooting painfully remind us, othering causes real harm. By viewing groups of people as not only different, but less-than, it becomes easier to exploit, ignore, blame, and in the most extreme instances, destroy them. As much as the “model minority” trope might urge us to think that anti-Asian racism disappeared after the Second World War, it’s still very much a part of the American cultural landscape, as the pandemic and the desire for an easy scapegoat has made brutally apparent.

This is why representation is so important. As Abnet argues in his conclusion, from the sublime discography of Janelle Monae to the latest seasons of Westworld, Black artists, Indigenous creators, and others challenge the monolithic whiteness of robots. They create works that aren’t afraid to show the horrors underpinning the American Dream while offering alternative versions of freedom and self-actualization.

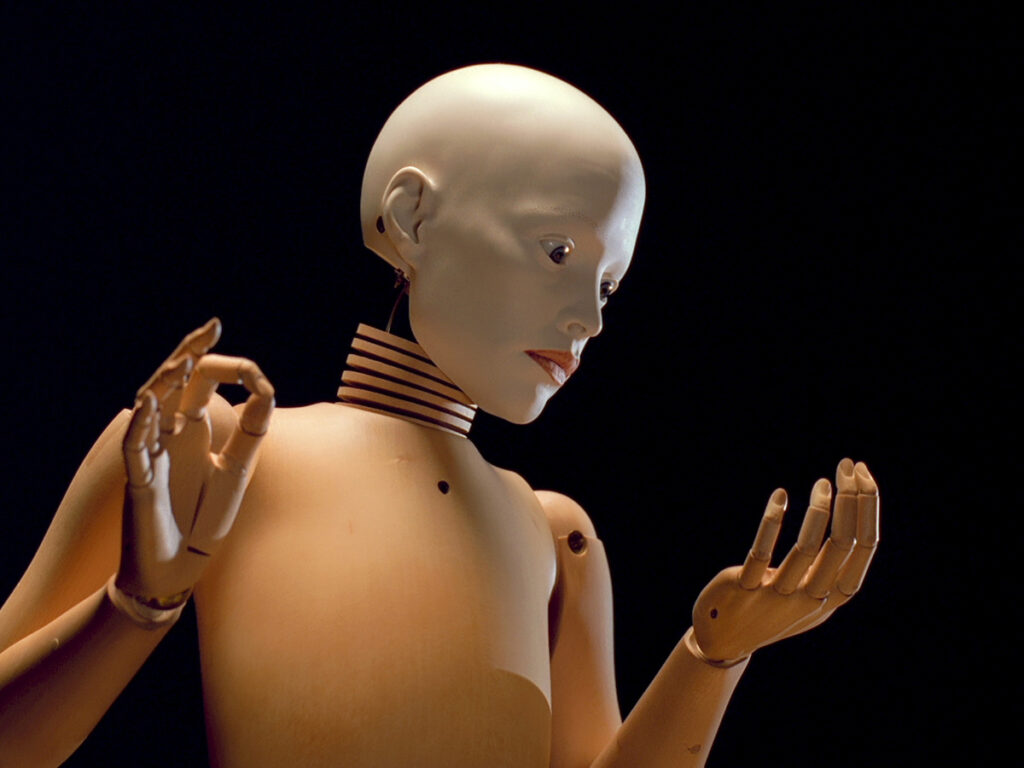

Silent stop-frame animation. 2 minutes. The sculpture featured in this short animation is Pupil, 1987-90,

porcelain, glass eyes, carved wood (Swiss pear), brass. Half life-size. Dimensions vary, eyes and all joints movable. This piece is an example of the kind of work we’d like to feature from King’s oeuvre, though I won’t give away which pieces we’re specifically considering. Stay tuned for a future post.

While my ongoing research has been delving into some pretty complex areas in terms of robots, intersectionality, and cultural history, we’ve also started having conversations with artists we’d like to feature in the show, including Richmond-based multimedia artist Elizabeth King. Her practice explores the nuances of physical movement, thought, and the complex emotional experiences stemming from both. King is best known for her exquisite multimedia sculptures and animations. Working at the intersections of puppetry and human anatomy, she creates intricate articulated sculptures from wood, clay, and metal. She then animates these pieces through painstaking stop-motion animations, with each subtle gesture implying physical as well as mental movement such as daydreams and other wanderings of the mind. Intimate in scale and meticulously rendered, these multimedia works exist as performance as well as sculpture, transforming their vitrines and display cases into theaters. While not specifically robots or automata per se, her work converses with both through their own musings on movement and emotion. Talking with her and sharing ideas has made me all the more eager to get vaccinated so that I can see these arresting works in person.

The Barry Art Museum staff and I have also continued refining the exhibition’s organizational themes. Although we want the show to address a broad range of ideas, we’d also like to maintain some kind of coherence and not have the exhibition balloon into a kitchen sink scenario. So after comparing notes, we’ve decided to pursue the body as another organizing thread, from the humanoid designs of robots and automata to the ways in which robots shape how we understand our own bodies. Beyond recognizing the largely anthropomorphic focus of the Barry’s automata holdings, concentrating on the body also enables us to explore medical robots, prosthetics, and other scientific equipment.

Moving forward, I suspect the Zoom conversations will continue to increase in frequency. On Tuesday we’ve got a session planned with the Morris Museum, which has one of the largest public automaton collections in the United States. Later this month, we’ll be meeting with our interdisciplinary advisory board for the first time. And Joseph Morris, an artist whose abstract works explore the intersections between machinery and emotion, has expressed interest in a preliminary conversation.

So onward we go!