From August 5th to the 20th, I served as a classroom instructor (CI) for the immersive Keio/W&M Cross-Cultural Collaboration. For two weeks, twenty-five students from Japan’s Keio University visited William and Mary to practice their English skills, learn about United States history and society, and complete a research project comparing American and Japanese cultures. Today, I’ll tell you about my experience as a first-time instructor in this special program.

Keio students had a full schedule from the moment they landed at Dulles, and for all activities, students were expected to speak, write, listen to, and think in English. A typical day included a morning lecture on a topic pertaining to American culture, a dialogue class, lunch, an afternoon research session at the library for their group projects, and dinner. Toward the end of their stay in Williamsburg, students presented their group projects to the rest of the class, with each presentation taking about 20 minutes. Topics included elementary school transportation, perceptions of elderly drivers, the nature and function of vending machines, cash-spending habits, and women-only transportation.

The dialogue class was my biggest responsibility as a classroom instructor. For an hour an a half every day, we’d talk about the content of the lectures we’d just heard, with the guest lecturer stopping by for 15 minutes to answer questions. I usually started the class by having students write down a question for the guest lecturer, as students could refer to the text when talking to the professor. While we waited for the professor to stop by, I’d have the students go around the room and share a thought or observation about the topic. Once the professor arrived, I’d have the students ask their questions. Since we usually couldn’t get to everyone in 15 minutes, I’d have the remaining students ask their questions to me, and I’d answer them as best as I could. I also had students occasionally break into pairs or small groups to talk about specific discussion questions, as it was less intimidating than speaking in front of the entire class. Finally, we’d usually wrap up with a few presentations of memory books, which were small autobiographical PowerPoints that each of the students had made before coming to the United States. Through these different exercises, I was usually able to get each student to speak in English at least three times during each class. In addition to dialogue classes, I also read and graded online journal entries from each of the students, where they would analyze their experiences in America using the lectures, dialogue classes, and comparisons with Japanese culture.

My other job was to transport students, which meant I drove my dialogue class around town in a 12-person van. I mostly drove around Williamsburg, but we also took trips to Newport News and Richmond. Driving the van was initially a little scary, I’ve driven U-Hauls full of art before but it’s different when you’re responsible for the well-being of 12 other people, but it got easier with practice.

Attending a special lecture at the Canon Factory

Group excursion to Colonial Williamsburg

Attending a baseball game with the Richmond Flying Squirrels

In addition to the regular lectures and dialogue classes, there were also several field trips. During the two weeks, we toured the Canon factory in Newport News, went shopping in Richmond, and attended a baseball game. On a free day, students visited Colonial Williamsburg, York Beach, and went shopping at the Williamsburg outlets. On Sunday morning, we all went to different church services to see religion in practice in America, with my group going to New Zion Baptist Church. That was a particularly special experience for me, as it was the first time I’d ever visited a black baptist church.

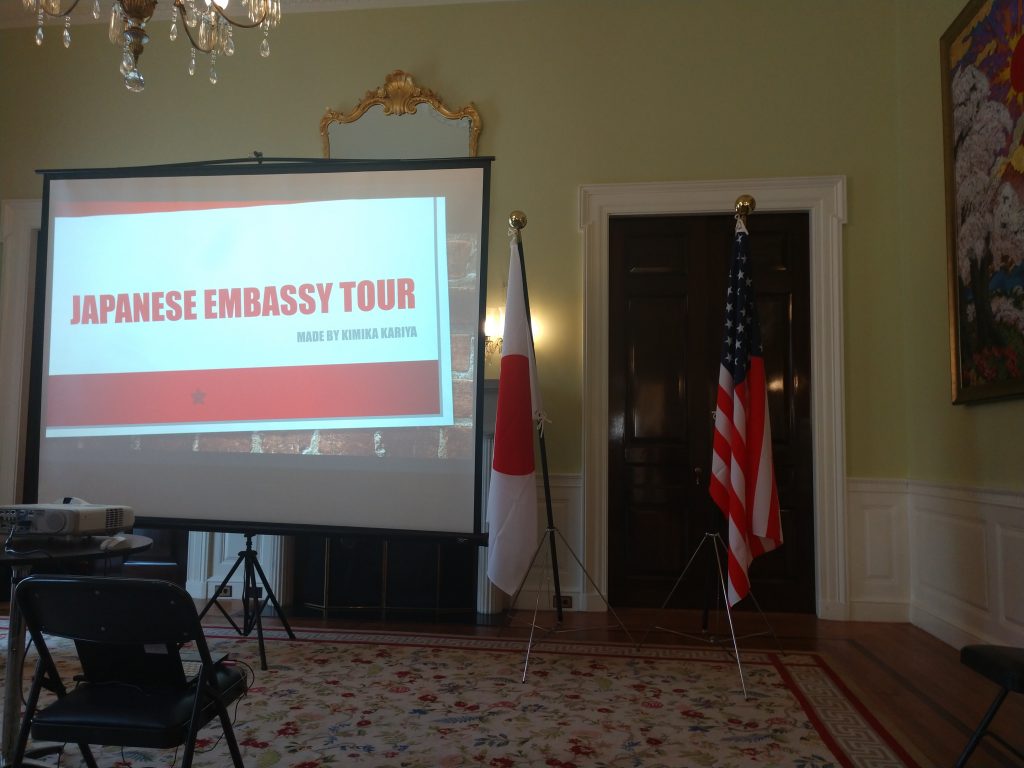

The culminating experience was a trip to Washington, DC. During the next few days, we visited different Smithsonian museums, took a walking tour around the monuments, and visited the Japanese Embassy. After an emotional farewell dinner and talent show, students headed back to Dulles Airport, while William and Mary Students returned home.

The former ambassador’s residence at the Japanese embassy, 1932.

Originally used as a residence, this elaborate home is primarily reserved for special occasions nowadays.

Japanese tea house at the Japanese embassy, 1960.

Originally built in Japan, the tea house was shipped to the United States and reassembled here.

The program challenged me in a lot of ways. During the first week in particular, I worked a lot of 12-hour days. While I wasn’t with the students the whole time, I couldn’t go home either, since I needed to be available to drive the van. As an introvert, it was challenging to be “on” for such a long time, even when I knew it was only for two weeks.

My days were also filled with active listening. Since I wanted my students to feel confident when speaking English, I needed to pay extra attention to what they were saying to make sure I understood what they wanted to communicate. I can be a little hard of hearing as it is, so this meant I had to work extra hard on my end to make sure I could hear through my students’ accents, as well as mentally process their often very formal questions into more idiomatic English for myself. I also had to put more thought into what I was saying to make sure my students understood me, as I didn’t want them to feel lost or confused. All of this active listening and speaking was very draining mentally, so by the time I got home every night, I had to keep asking Brandon to repeat himself because I couldn’t remember anything he was saying.

Beyond the physical and mental challenges of so much active listening, the content of the conversations themselves could also be difficult. Since I had the most advanced group of English speakers, we could discuss the lectures pretty deeply, and a lot of them delved into serious subject matter. The lecture on race relations in America was particularly intense, as I had to explain the systemic nature of American racism to students who had not grown up in this particular environment or culture. The students, meanwhile, learned that the United States is not the ideal country portrayed in its patriotic mythology, but a highly complicated place that has yet to live up to its ideals. Indeed, “it’s complicated,” became my catchphrase at every dialogue class.

I also learned a great deal from my students. During our dialogue classes, some of my students grounded the lecture material by comparing the topics with examples from Japanese history, which offered me new perspectives. Meals at local restaurants became opportunities to talk about different food cultures, and food accessibility. We also talked a lot about differences in transportation, hobbies, and why stores in Williamsburg close so early. Since a lot of my students were from Tokyo, Williamsburg was comparatively more provincial and rural, which brought its own experiences and challenges.

Over the course of our two weeks together, I learned a lot about my students, particularly through their memory book presentations. Yu Horiguchi loves listening to vintage jazz. Koryu Ikeshita enjoys rap and hip hop. Fumiho Tanaka has lived in several different places, including Mexico City and New York. Manai Suzuki would like to work at a TV station when she has finished college. Haruna Fujimaki is learning how to do magic tricks with playing cards.

I also had plenty of opportunities to watch my students engage with their peers during classes and projects. Kaori Sano was extremely supportive of her fellow students, particularly during the focus group projects. Miu Nishimura and Maho Arito always asked thoughtful questions in the dialogue classes. Kimika Kariya rounded out our experience by giving a lovely presentation on her experiences with the program at the Japanese Embassy.

Ultimately, the Keio program was a very rewarding experience, not least because of my wonderful coworkers. Ravynn Stringfield, the program director and experienced CI herself, was meticulously organized and made sure we always had rosters and checklists that made field trips and other excursions much easier to implement. She also suggested the pairing and sharing technique that became a key part of my dialogue classes, and always took care to check in on our mental and emotional well-being. Laura Beltran-Rubio, the assistant director, also provided plenty of emotional and logistical support, whether she was picking up food for catered meals, or figuring out how to get baseball tickets for more than 30 people. My fellow CI instructors, Chris Slaby and Adrienne Resha, were equally helpful, sharing potential discussion questions and other ideas for dialogue classes. Chris, a CI veteran, was my go-to person regarding anything pertaining to teaching with Keio, while Adrienne suggested the idea of writing down discussion questions for guest lecturers. They all helped me become a better CI.

The undergraduate staff members who worked with the students as Peer Advisors (PAs) were also indispensable. They, along with the directors, stayed at the same hotel as the Keio students, so they were always available if someone needed assistance (CIs, by contrast, got to go home every night, aside from DC). During the afternoons after Dialogue Class, they worked directly with each of the focus groups to ensure that everyone contributed and remained on task, and kept us CIs informed of their progress. They also coordinated most of the meals, deciding where to take the students to lunch each day, for instance. They also served as navigators for field trips, reading off directions to me while I focused on driving the van.

Keio is definitely a collaborative adventure, and I could not have completed my job without the help, support, and humor of my colleagues.

The Keio program pushed my limits in so many ways, but it also expanded my skills and introduced me to new perspectives. Engaging in dialogue classes every day was especially helpful, as I’ll be a Teaching Assistant this coming semester, but I also benefitted in other ways. The Keio program is an exercise in endurance and flexibility, all taking place in a rich environment of cross-cultural dialogue and exchange. It demands patience, versatility, and above all, an open mind and the willingness to listen and learn.

I’d like to think that my students learned something from their experience here in the United States. I certainly learned a lot from them, and I will always be grateful for that.