At the beginning of the semester, Professor Donaldson, the instructor for Utopia in the Americas, invited me to give a short lecture on any topic relating to American utopias. While I’ve given plenty of gallery talks and lectures to museum audiences, I haven’t had as much experience in the college classroom, so I was eager for the opportunity to apply my skills to a new setting. Last week then, I gave a half-hour talk about art colonies, a topic I’ve been casually researching since at least my time in New Mexico.

I chose art colonies because I saw a lot of parallels with intended utopian communities like Brook Farm. Art colonies are communities of artists, writers, and other creatives who come together with the intention of producing new work together in a supportive environment. Like utopian communities, they take issue with the world as it currently is and seek to improve it by providing a creatively stimulating environment. Art colonies were especially popular in Europe and the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before World War I. In the US, you could find them in New England, the Midwest, the West Coast, and everywhere in between.

Since this was an art history-focused discussion, I developed a PowerPoint presentation that let me share several images. I also provided an outline of my notes to the class so students could have a basic reference to follow. At the end of my notes, I included a brief list of book suggestions in case students wanted to read further.

As for the talk itself, I divided it into three parts, and clearly stated when I was moving on to a new topic. After defining art colonies, I described the historical context in which they developed. I highlighted the following interconnected trends:

- Camaraderie: 19th-century American artists studying academic painting finished their training in Europe whenever possible, going to Paris especially after the Civil War. These American students often socialized together while abroad, and wanted to recapture that camaraderie when they returned.

- Anxieties about change: The United States in the second half of the 19th century experienced a lot of rapid change in terms of immigration, industrialization, women’s rights, and so on. A lot of white, middle-class people in particular experienced anxiety over this, and responded through reactionary, nostalgia-driven movements such as Arts and Crafts, the Colonial Revival, and the City Beautiful Movements. All of these creative responses were intended to reintroduce a sense of order and human agency over the seeming chaos the defined rapid urbanization.

- Nationalism: During the late 19th century, nationalistic pride cropped up in both the United States and Europe as countries looked to their folk cultures for the roots of their identities. Over here, American artists took increasing interest in painting American landscapes or incorporating folk art into their work as a means of asserting an art that was distinct from European examples.

I emphasized the historical context because Professor Donaldson had already talked about it in previous lectures. I wanted to show students how this same context extended to art colonies while reviewing concepts we had already talked about through lectures and discussions. Once I sketched out this background, I then briefly talked about three different communities:

- Taos/New Mexico: artists have been coming here since the late 19th century. During the early 20th century, various groups cropped up, many of them focused on seeking out exhibition opportunities. The first generations of artists were primarily European trained and applied their training to painting New Mexico’s landscapes and indigenous cultures. The most overtly utopian iteration is arguably the salon of Mabel Dodge Luhan, who invited leading Modernists such as Andrew Dasburg, George O’Keeffe, and Marsden Hartley to visit, not to mention writers such as D.H. Lawrence.

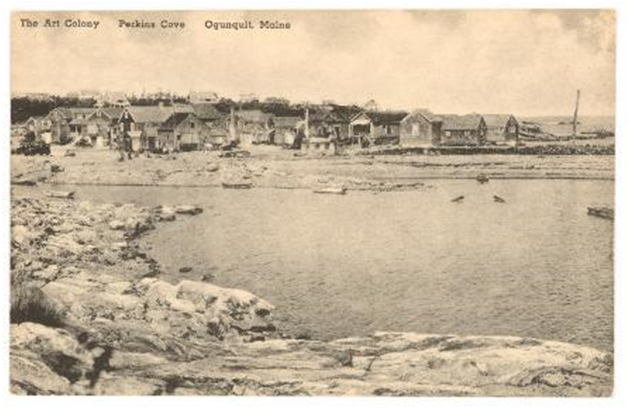

- Ogunquit, Maine: In 1898, painter Charles Woodbury began frequenting the Perkins Cove area of Ogunquit to set up a summer painting school focused on rendering the landscapes and peoples of the region. In 1911, artist Hamilton Easter Field bought a series of fishing shacks and began renting them out to artists. Whereas Woodbury focused primarily on landscape painting, Easter Field became more interested in Modernist abstraction, and sometimes decorated the shacks with folk art to inspire renters. In the 1950s, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art opened, highlighting the artistic activities of these two groups.

- Byrdcliffe, New York: This was the most overtly utopian of the groups I talked about. Founded by architect Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, artist Jane Byrd McCall, and artist Bolton Brown, it modeled itself on the Arts and Crafts Movement, with guild-like workshops underpinning its social structure. It continues to operate as an Artist-in-Residence program.

There were several other examples I could have discussed, but these were the ones I’m most familiar with. With Taos in particular, I wanted to get out of the Northeast and highlight what was happening in the Southwest, since the course has primarily concentrated on communities east of the Mississippi.

I wrapped up with a brief conclusion. I argued that while limited funding or clashing personalities often prevented art colonies from becoming long-term, autonomous communities, we still benefit from art colonies in the form of artist-in-residence programs. I described these as permanent communities of temporary residents, places where artists can focus on their work, bond with their fellow residents, and return to their regular lives to share their new work.

This talk was a lot of fun. When I was a curator, I always liked giving gallery tours and brown bag lunch talks, so I enjoyed having a chance to talk about art history again in an educational setting. Public speaking has always been one of my strengths, so I’m always eager to put those skills to use when the opportunity comes up. Professor Donaldson also enjoyed the lecture so much that she recommended I consider developing it into an undergraduate seminar. I’d definitely like to teach a class at William and Mary in the future, so it’s certainly an option I’ll keep in mind moving forward.