For the last two weeks, my posts have reflected on the current pandemic, but today I’d like to share some good news: I’ve recently published an article in Arts, a peer-reviewed, open-access journal. You can read the article here.

While I’ve published my work before, this is my first peer-reviewed work. This means that other scholars have read the manuscript commented on it, and ultimately considered it worthy of publication. Better yet, Arts is an open-access journal, which means that anyone can read its contents without having to pay. As someone who’s experienced the frustration of paywalls, I’m glad that I can share my work with anyone who’s interested. It also means that my work will have a better chance of getting read and cited because there’s no fee that might turn off potential readers.

So what’s this article about? The subject is a collection of World War II drawings from New Mexico artist Howard Cook (1901-1980), and more specifically a group of works collectively titled Self-Portrait in a Foxhole. For three months in 1943, Cook served as an art correspondent in the South Pacific as part of the federal War Art Unit, a government initiative intended to document the war. During those three months, Cook sketched Allied soldiers engaging in everything from watching movies to digging trenches. In the case of the Self-Portrait group, Cook shows himself taking shelter during an air raid while participating in the Invasion of Rendova. In the article, I argue that the Self-Portrait group explores the war experience through the lens of vulnerability, a theme that recurs throughout his war drawings.

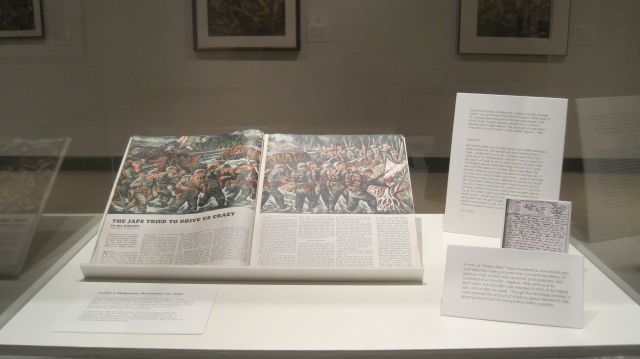

This article developed out of an exhibition I curated in 2015. The Roswell Museum has a large collection of Cook’s art, including the war drawings, along with the correspondence Cook wrote during his assignment to his wife, fellow artist Barbara Latham (1896-1989). Roswell has a large veteran population and fond memories of the Walker Air Force Base, so I knew an exhibition on war art, especially one on view during the 70th anniversary of World War II’s end, would appeal to a lot of visitors. In addition to showcasing our collection, I borrowed a few painted works from the art collection at the New Mexico Military Institute. I also featured a 1943 issue of Collier’s magazine, where Cook had some of his art published. For the actual text labels, I quoted from Cook’s letters whenever possible, allowing readers to learn about the works through his perspective.

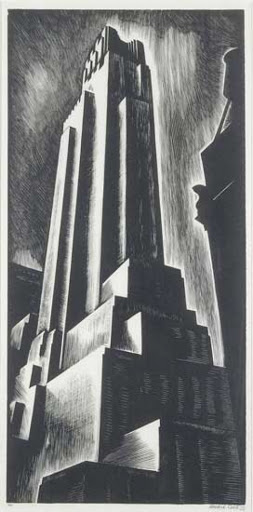

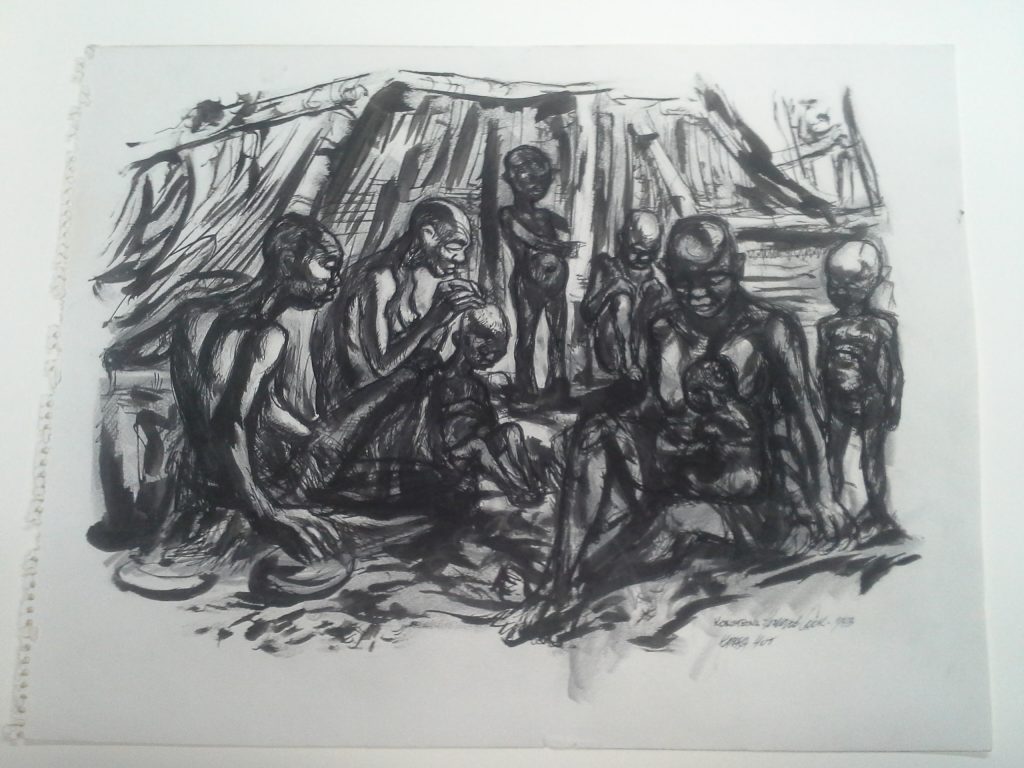

While I may have started out this exhibition with visitors in mind, I ended up getting really interested in the works myself. I’ve always liked Cook’s work, but the war drawings are especially interesting because they’re something of a departure from his earlier works. Cook started out his career working in a Precisionist style, and he always drew in a clear, lucid manner with an ample amount of reflected light to give his work a luminous quality. He continued using that style for a lot of his war drawings, but he also experimented with a more gestural, expressionistic style. In works like Two Men in a Foxhole, shown above, Cook uses thick strokes of white pigment to suggest the forms of the two men, their white flesh standing out vulnerably against the ink wash background. While Cook relied on strong contrasts between light and shadow to bring clarity to his compositions, there’s a raw quality to the Rendova drawings that you don’t always see in Cook, and I thought that was worth exploring further.

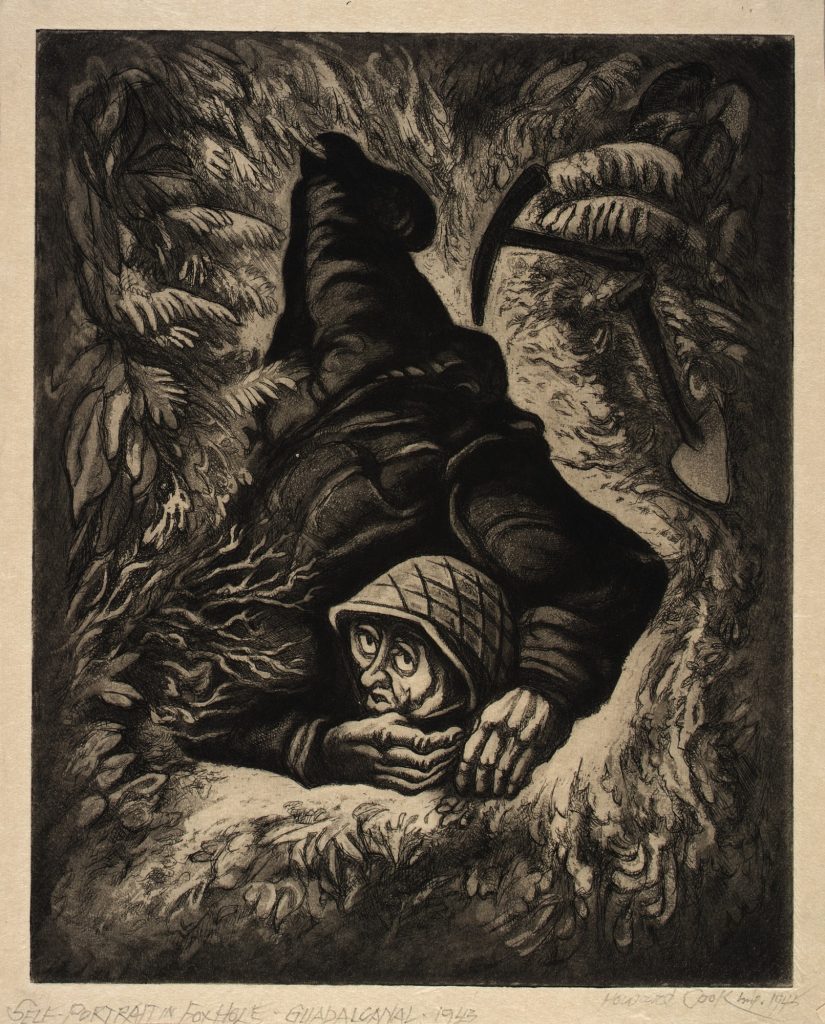

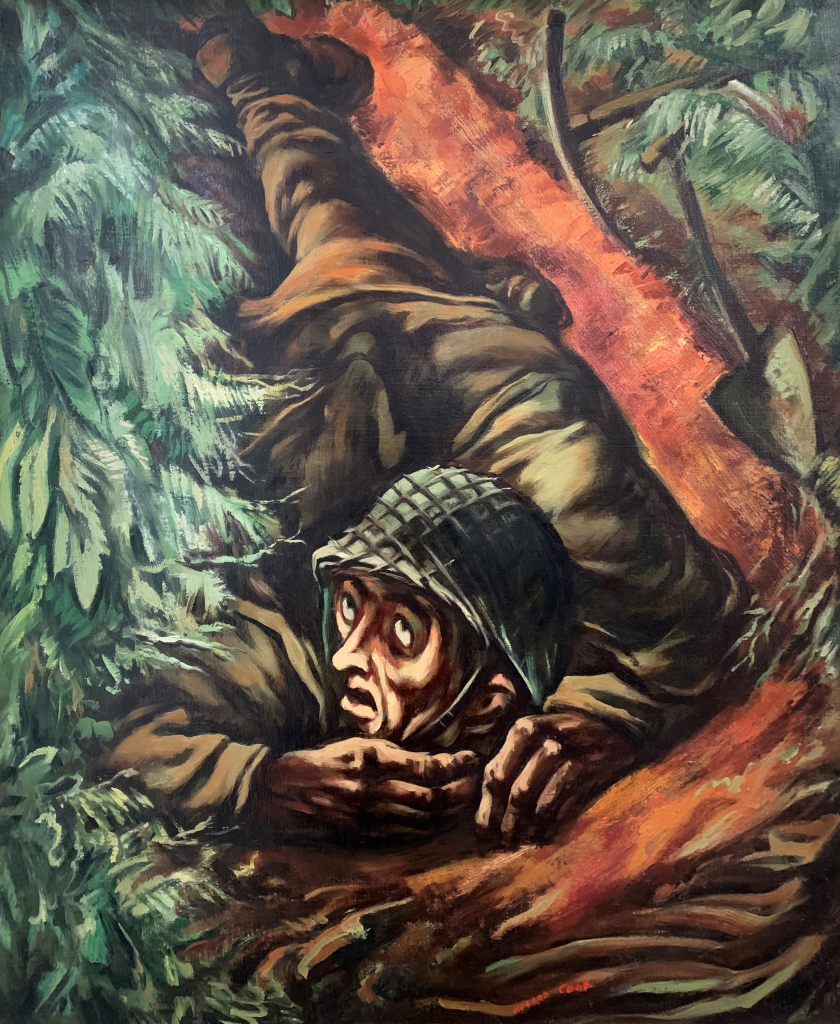

What especially intrigued me about the Self-Portrait group was the artist’s decision to depict himself in a moment of vulnerability. Cook doesn’t show himself digging the trench, or running off the boat during the initial Rendova landing. Instead, he’s showing himself taking shelter from artillery fire, something he couldn’t actively fight back against. I thought this vulnerability was worth exploring and decided to write about it.

Same Self-Portrait, different media. Left: Self-Portrait in a Foxhole, 1945, etching and aquatint on paper. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Right: Self-Portrait in a Foxhole, 1943, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the New Mexico Military Institute.

I first floated the idea of a potential essay in 2015, when I presented a conference paper at the Southwest Art History Conference in Taos. It was well-received there, so I sent the paper to a professor I knew at Williams for suggestions and began expanding it into a manuscript. I was on a roll, but after the exhibition opened, other projects and tasks began demanding my time. I decided to shelve the piece until the right opportunity came up to revisit it.

That happened in the summer of 2019, when the Williams College listserv forwarded a call for papers for a special issue in Arts journal. The editor was especially interested in works that dealt with the Pacific Theater, so I sent in an abstract because I figured I had nothing to lose. They accepted it, so I spent the next few months reworking the piece. In July, I was notified that it was accepted, so I started work by making a schedule. Since the manuscript was due in early December, I worked backward to July to make sure I had plenty of time to finish. I ultimately decided to dedicate an hour each weekday morning to working on the piece, so that I would make steady progress while having plenty of time to focus on my coursework.

I started by taking the original essay and reading it all the way through. After rereading the original essay, I made notes on how to improve it. I then refreshed the research (having access to a university library and all its academic resources made that a lot easier), which including rereading Cook’s letter as well as finding new secondary literature. I then wrote three different outlines: one for the original essay, one for the envisioned new essay, and one that combined the two. I then spent the next few months reworking and expanding the 2015 essay. The manuscript then went through two rounds of peer reviews, and after each round I incorporated their suggestions. The final essay was substantially different from the 2015 piece, but having a draft that I could then rework made the whole process much easier.

It was interesting to revisit this piece, because it showed me how much my interests have changed over the last few years. I’m proud of this article and I’m happy to introduce RMAC’s art collection to a scholarly audience, but my focus has shifted since I first started working on it. if I were to write this piece now, I’d focus on Cook’s decision focus on white soldiers rather than indigenous populations, aside from a few preliminary sketches. As I’ve learned, what’s not shown is as important as what is.

All that said, I’m pleased to have this essay out there now (and very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful commentary), and I hope it will open up more scholarly inquiries into both Cook’s work and the Roswell Museum collection more broadly. It’s got some great works that scholars would benefit from studying.