Since the beginning of the year, I’ve been making an effort to be more consistent with my artistic practice. After seeing that I could make something every day with last year’s abstraction challenge, I’ve tried to draw or paint something new several times a week. I often work on these projects in the evening, as a way of unwinding before going to bed, or on the weekends as a way of taking a break from work.

A key part of what I find enjoyable in making art is knowing that there will be an end result. Whereas academic work can take months, often years, for tangible projects to manifest, creating a new drawing or painting enables me to watch my results unfold more quickly. Making hatch marks or brush strokes is calming, yes, but there’s also satisfaction from seeing an artwork come to fruition. In other words, downtime feels worthwhile because it’s productive in a very literal sense. Even if the work isn’t for sale, just knowing you’ve made something, whatever its purpose, offers a sense of accomplishment.

Since I’ve been making art more consistently, it’s gotten me thinking about the role of creative productivity in American culture. From adult coloring books to knitting circles, guided creativity is as popular as ever today. Whatever you choose to make, you’ll have something to show for all your downtime. In a productivity-focused culture where doing nothing is discouraged, despite its benefits, craft projects legitimize leisure by enabling us to show the tangible results of our relaxation.

Not coincidentally, crafting and its related activities are entwined with wellness. After all, what better way to affirm the necessity of the arts than through connecting them to physical and mental health: a quick search online will display numerous articles touting the benefits of arts and crafts on mental wellness. At William and Mary and numerous other institutions, craft circles have become an important part of the wellness curriculum.

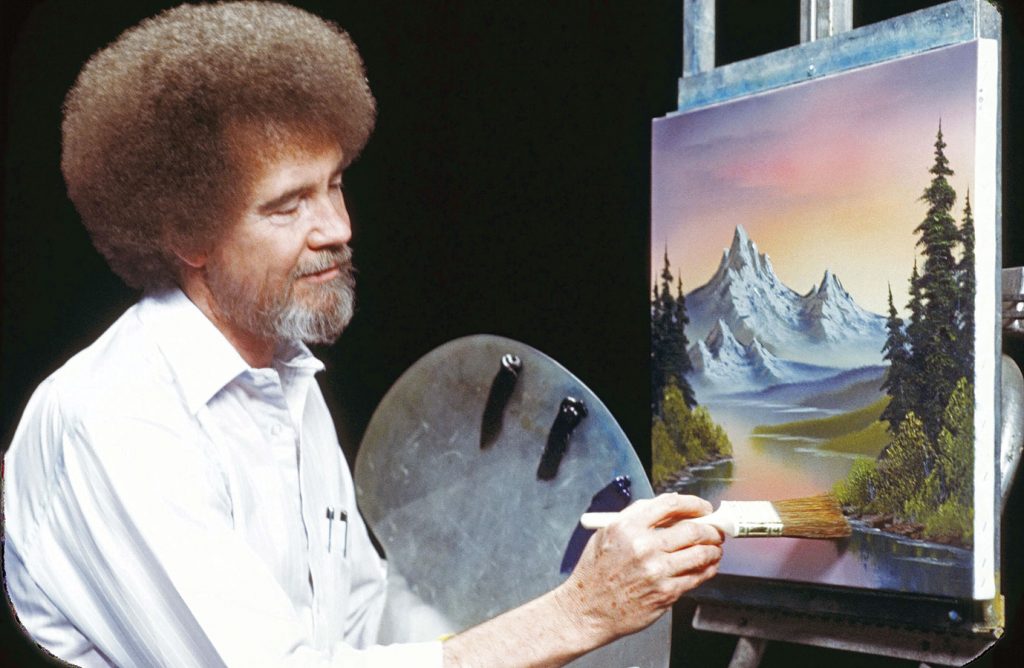

Not that this is anything new. Take a look at American visual culture and you’ll find a rich history of crafting and what I call guided creativity. When I was in Roswell, everybody was into ceramics (including myself). When my mother was a college student in the 1970s, macrame was popular. And let’s not forget about Bob Ross, whose positive messages of happy little trees and joyful mark-making have been experiencing a resurgence thanks to the Internet.

Nor is guided creativity a recent phenomenon. Art historian Jennifer Jane Marshall has traced the popularization of soap-carving during the Great Depression. During the 19th century, theorem painting was a popular craft, especially among young women. These art forms may utilize different media, and indeed their very status as art has been questioned by both their contemporaries and subsequent historians, particularly when largely practiced by women. What they all share, however, is an emphasis on results. Whether you’re following a paint-by-numbers set or knitting a scarf, these techniques promise practitioners both the thrill of creativity and the security of guaranteed results. In short, their creative experiment is all but promised to succeed, rendering their time useful.

What drives this need for productive creativity? Some would argue that it reflects the capitalist nature of American culture, which places an emphasis on results and profit. That scarf or theorem may not be for sale, but it is the tangible result of work, so you have something to show for all the time you put into it. Indeed, entire industries have developed around guided creativity, with art supply stores offering coloring books, yarns, and other materials to stimulate one’s crafting prowess. Others would argue that guided creativity further enables the capitalist machine by distracting practitioners from the systemic economic and cultural dissatisfaction that permeates their lives. Who has time to rage against the machine when they’re preoccupied with knitting a hat? Still others would posit that guided creativity serves as a means of controlling creativity energy by funneling it into predetermined forms. You may be free to choose your own colors or patterns, but the basic structure and form of the activity you’ll do has been predetermined for you. In short, you can be creative so long as it doesn’t challenge the status quo when it comes to cultural forms. Color within the lines.

Not surprisingly, I’ve been thinking about guided creativity through the lens of the Community Art Center Project. In addition to hosting regular exhibitions, these centers also offered free art classes, with the intention of teaching adults and children alike how to paint, draw, or sculpt. As Victoria Grieve argues in her book The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture, there was a commercial element to this effort. The Federal Art Project didn’t expect all of its students to become professional artists, but it did aspire to encourage sales by instilling art appreciation into visitors through education. Making art, in other words, would not only enable people to express themselves creatively, but would also help them to appreciate art as a commodity they could purchase for their own homes, having learned how to enjoy looking at it through their classes.

While I don’t disagree that there’s a commercial aspect to the Community Art Center Project, I also think there’s something else going on here, something more basic. Making art, in my opinion, is often a distillation of what we experience in everyday life. Not so much in subject matter per se, though that often happens, but rather in the process of experiencing the world through sensory means. We experience and change the world through our bodies. Whether we’re touching a blade of grass or chewing food, our bodies are our means of both experiencing our and changing our surroundings. What better way to assert your presence in the world than by making something, whether it’s with your hands, your feet, or your mouth?

Not coincidentally in my opinion, the significance of craft and the handmade surges alongside massive technological change. During the turn of the twentieth century, for example, the Arts and Crafts Movement developed in Britain and the United States in response to a perceived decline in manufacturing quality due to industrialization. By reviving the craft-driven, handmade traditions of medieval guilds and workshops, designers like Gustav Stickley and William Morris argued that they could produce superior designs that emphasized the human presence.

Nowadays, in a world where smartphones and other screens connect you to virtual worlds, you can still find people typing poetry on vintage typewriters or baking bread as a means of achieving what they consider a more authentic experience. That desire to exercise positive change through our bodies, to a leave a literal mark on the world, persists. It’s frustratingly ironic that the arts are the first to go when it comes to funding because they’re considered nonessentials, but history has shown repeatedly that they are in fact important to a sense of self and well-being.

So is guided creativity nothing more than a commercial scam designed to keep us complacent while the capitalist machine rages on? Perhaps, but I think there’s something else going on too. In making art, hope to leave a trace of ourselves in the world.

Regardless, I’m going to keep making stuff.